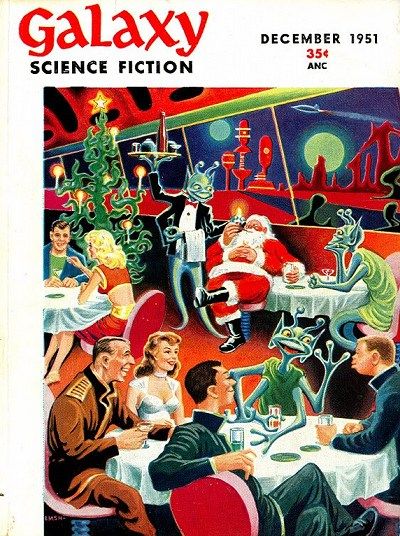

This short story of a mere incredible 15 pages first appeared in the December 1951 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction. Folks, this is what speculative fiction is all about. It fits to the highest degree I have yet encountered where imaginative scientific speculation balances with real human interest, where fictional skills give a plausible and fascinating account of how the dramatic interaction of certain physical laws of the universe can directly affect the nuclear family, our most essential social and psychological unit. What if a black dwarf star, its own system of planets long since obliterated when it swallowed them up in an earlier red giant phase, were to pass in its orbit about the galactic center through our solar system, most specifically among our inner planets? What if its massively condensed gravitational force tore us free of the Sun's primordial hold upon us and drew us out into the depths of coldest empty space, the Earth now a slave to a dead but tenacious bone of a star whose only indication to the human senses is its circular blotting out of the stars as we face it on what amounts to a nocturnal "day". Would anything survive such a catastrophe?

Leiber keeps our focus on a single family, from the point of view of the brother/son, which otherwise consists of a mother, father, and sister. We understand this world through the boy, what he experiences, what he has learned from his parents, and how he interacts with his family members. For all them, they are all they know that remains of life. The world has passed through massive earthquakes as it experienced the violent gravitational shift from one orbital orientation to another. It has lost its atmosphere in this process. It's atmospheric gasses have fallen to the surface as snow in ordered sediments according to their susceptibility to solidification amidst steadily falling temperatures, as the black dwarf star has drawn the Earth farther and farther away from its former reliable source of warmth: the Sun -- which is now a star unremarkable from any other in the night sky. The family survives on huge stockpiles of non-perishable food left unconsumed by the massive die-off of humanity during the crisis of tug of war between our living star and the dead invading star, and the ensuing planet-wide ice-age. They also live on blue-white oxygen in the form of a distinct layer of snow, which the boy is now old enough to fetch on his own with a metal pail.

The boy's family lives in a quake-damaged apartment building where his father, a former scientist, has created a room protected by suspended layers of cloth and mattress barriers to slow the escape of oxygen. The structural deviations in the building from the period of rampant earthquakes makes hermetic sealing impossible. The oxygen is released into breathable gaseous form by melting it on the fire, whose fuel source is lumps of coal (ready supplies of which could have been gathered from innumerable basements back in the early '50s when this story was written because home and apartment building furnaces were directly powered by coal rather than indirectly, as many are now). Outside the family's "cooked" atmosphere, there is not much in the way of sound, especially when one leaves the building and enters the outside, where there is no free air to carry sound, no wind or breeze. The father has constructed helmeted suits for their brief and necessary ventures outside their lonely little refuge. Our first-person-point-of-view character visually understands the world known to we readers only in terms of the illustrations in encyclopedias their parents gathered for the education of their children, for both he and his sister were conceived and born after the catastrophe.

Their parents sought to affirm their survival and their commitment to the continuation of the human species by having offspring of their own once they figured out a way to survive in the long term, hoping that one day they might discover others who might have seized upon similar ways to sustain existence. But the mother has abandoned this dream years ago, and where once she was the strong one who had helped keep the family alive when their father was laid up with an injury, now she has become a neurotically fragile being whom the whole family endeavors to comfort. The boy knows by first hand evidence that there were once others, because in their quests for supplies, they sometimes pass by other rooms in the apartment complex where human beings remain perfectly preserved in their moment of death, many in circumstances indicative that they had surrendered to the dire consequences into which the whole world had been suddenly plunged. The father is the chief storyteller, continually shaping and refining the legend of the world before and the world now as their children grow in maturity and understanding, and these stories are their chief form of entertainment.

This story, however, begins, when the boy on his daily chore to acquire another pailful of air catches a hint of light and a moving figure. The immediate reaction is not that of hope or rejoicing, but caution, guardedness, the controlled fear and carefulness of proven survivors. The boy retreats to tell his family, and the mother becomes so agitated, that the father brushes it off as likely an illusion created by the effect of the boy's flashlight and the oozing nature of viscous helium, which is present here and there in the extreme cold, taking on furtive, beguiling forms to the sensory-fractured perceptions of the human cognitive imagination in such a literally benighted world. The father, however, after interviewing him more closely, confides to his son that he may have indeed seen something "real". They go out to explore, which gives Leiber another opportunity to paint a fascinating and ghastly picture of their broader world. They find nothing more to substantiate the boy's report, but on their return, it inspires the father to give a more passionate telling of how everything came to be. The family is brought back to relative calm, the sister physically soothing their mother the while, who had grown afraid again when the father and son had gone out to investigate, despite her husband's bland assurances.

And then the calm is disturbed. At first by faint resonances, then indirect flickers of light of alien origin. The family unit goes on its guard, even though they have never known another animate being in all the years they have been together. The ending I will not spoil, but it is transformative. Even without revealing the ending, whose outcome could easily have been other than what the author has chosen given the circumstances already described, the reader is still left to ask: does it make sense to keep trying, even when all available evidence of hope is not at hand? In a world of ultimate uncertainty, does it make sense to gamble and have children, consigning them to a most uncertain destiny? Is creating and nurturing a family the most essentially beautiful thing to do in the face of an uncompromisingly ruthless universe, even after it has literally removed its sunny mask to reveal its awesomely dark nothingness? How long can the human psyche, whether it be that of an adult, a child, a male or female, endure social isolation and sustain its sanity, even in the benignly integrated relationships of tightly-knit disciplined, responsible interdependence?

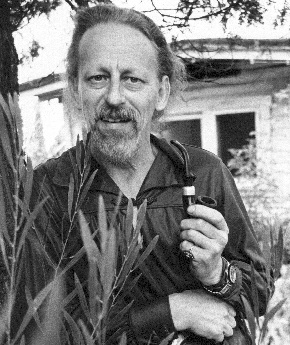

Mr. Leiber, you have created here a beautiful interweaving of scientific cosmological profundity and the humble centrality of our shared humanity as the sentient witness to it all. Here you combine palpable detail with astrophysical laws as understood through the filter of a bright child too young to grasp the technical language of science or its complete implications for reality itself. You, Mr. Leiber, are indeed a writer of subtlety and depth, and though you have been gone from this world for many years now, your special mind and soul live on through its literary impact upon we, your fortunate readers! This story can most easily be acquired in this latest collection: Selected Stories by Fritz Leiber; Published by Night Shade Books; Copyright 2011.

Sunday, April 8, 2012

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Review: "Two-Handed Engine" by Henry Kuttner

Comprising twenty-two pages, this novelette originally appeared in the August 1955 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. This tale explores several philosophical concerns whose specific permutations could only have arisen in our present technological age. Our relationship to machines, from Ancient times to the present, has always been to ease various burdens or onerous tasks of life, and soon thereafter to create greater uniformity and quality of products. More recently machines have been designed to solve problems of organization and order to maintain societal integration as human population densities have surpassed all previous norms. Machines have also been developed to make warfare more devastating and precise in its targets. Henry Kuttner projects all these uses of technology toward a logical future singularity of evolutionary unification whereby humanity surrenders its self-responsibility to computers and the robotic servants of higher artificial intelligence.

This may sound familiar, but in Kuttner's hands it has a different outcome than the typical science-fictional trope. In exchange for peace and stability, which the objective dispassionate synthetic mind of centralized planet-spanning computers can provide without error, humanity gives up self-governance. The computerized and wholly mechanized world supplies psychological satisfaction through virtual reality experiences transmitted by artificially induced trance states. All necessities are artificially manufactured and delivered as needed. Human society atomizes, as people become self-engrossed in personal whims and selfish pleasures. Machines exist only for humankind's physical health and egoistic pleasure. The moral compass of society loses its orientation as the need for struggle, competition, social discourse, human cooperation and emotional connection dissolve before computerized illusions of hedonistic and imaginative fulfillment. For this story, all this is already history. The author introduces us to a society that has just barely managed a slim generation ago to pull itself out of social implosion, by reasserting an active role in the material world. Human beings were failing to reproduce, because the underpinning social structures for basic human bonding had nearly entirely disintegrated. Faced with self-extinction, individuals came together to redirect the comprehensively mechanized-computerized world with a new fundamental program: enable human beings to become socially responsible again.

What these pioneers at rebuilding the mental construct of society face, however, is daunting: "conscience" itself has to be not merely re-learned but re-invented. The super-ego has to be reactivated. So in addition to dismantling technologies that provided for every comfort, pleasure and imaginative whim (so that human beings would be motivated to form social connections again with their fellows), negative reinforcement has to be introduced into a newly activated society that has been for so long in a technological womb of passivity. Here, Kuttner cleverly reinvents the mythological concept of the Fury in terms of a technological (and robotic) force of social control.

At this stage in the redevelopment of human society, people, while intellectually advanced, are still so morally infantile that murder is the essential form of moral corruption as people become re-accustomed to interacting with one another in complex ways. The title of the story is taken from a cryptic verse by Milton, who envisions that figure from Greek myth, the Fury, as a "two-handed engine at the door": the pursuing conscience of the person who mistakenly thinks he or she can escape the psychological implications of taking the life of another. In Kuttner's story, the Furies are robots that track down and follow those who have committed murder. The world is under pervasive sensory surveillance by a vast computer-mind maintained by a hierarchical human bureaucracy. An act of murder is inevitably discovered, and the perpetrator identified by the source of law and order: the wholly objective engine of artificial intelligence. The murderer then receives his or her Fury, a faceless, voiceless robot that follows them wherever they go, and keeps a vigil over them wherever they stay or rest.

These special robots will prevent their inmates from harming again, and at a carefully calculated moment, dependent on unknown factors of the individual, the Fury will execute the felon by any manner of assorted methods. The robotic Fury does not (and needs not) hinder the movement of its ward. This Fury of mechanical body can make of the entire world a prison for its charge, for the murderer can neither destroy it nor elude it. Its tenacious but serene accompaniment of its assigned felon is an example to all who observe the bizarre pair of the cost of taking the life of another: an act of harm, as the author points out, that cannot be practically undone.

In the story at hand, the supporting character, Hartz, a high-ranking administrator, induces a maladjusted citizen, Danner, into committing an act of murder, by demonstrating that he has the mathematical programming ability to undermine the normally unerring directives of the master-computer to impose the tenacious Furies upon guilty members of society. Hartz is a complex figure, despite not being the central character, for he believes in the moral rehabilitation of humankind so that it might not regress and lose its will to achieve character and reproduce itself. However, he is frustrated in being the penultimate controller. Hartz wants to be the master controller in this new alliance with the more perfect computerized/mechanized coordinators of human civilization. He still retains the regressed impatience of the id needing immediate gratification, and so, for all his sophistication of responsibility, he has not the restraint of desire found in a fully evolved human consciousness. The man above him, in short, is a mere hindrance, rather than a respected superior partner (in short, a recognized fellow human being) in the new project to rehabilitate humankind.

In the central character of Danner, Hartz sees a man even less evolved than himself, who can be persuaded to commit the very act that the institution to which Hartz belongs seeks most primarily to correct. As for Danner, he belongs to the last generation to enjoy the previous era of no psychological or physical challenges, and he lived long enough in that former reality to have it deeply imprinted on him. Thus Danner is incapable of fully embracing or finding higher satisfaction in the new reality, which requires effort and puts character-building limits on the boons of existence. Danner is deceived into believing that Hartz will use his hacking ability to derange the moral directives of the master computer, but Hartz knows that if he acts upon his knowledge, he will create a fault that may unravel the whole system of social control and thus humankind's general rehabilitation.

Despite his selfish ambitions, Hartz ironically has evolved enough to recognize that if he allows his faulty super-ego to have its way too far, it will ultimately defeat the purpose of the whole philosophical revolution to put a socially-responsible humanity back on its feet. So Danner ends up with a Fury as his constant silent companion, until the unknowable date when the robot will receive the algorithmic command from the central computer to destroy Danner. Yet Danner never succeeds in acquiring an inward sense of moral guilt, only an outraged resentment that his master-conspirator has somehow failed to protect him from the very fate that he had been guaranteed not to suffer. In return, he has gotten the promised unlimited source of wealth with which to pursue the pleasures Danner once knew in his youth before such things became rationed and contingent upon personal effort and social success. But where is the satisfaction when one is condemned to a mobile (though invisible) spot on Death Row?

Danner ultimately descends into murderous madness, as his unshakable Fury makes him an outcast even when his fellow human beings are willing to share his company, for his ubiquitous warden makes him attractive only to those who connect with him because of their superficial fascination with his impending doom. In the end, Danner seeks to slay Hartz, who can no longer put him off with promises to discover the reason for his failure to scramble the code of computerized justice and allow his minion to escape his punishment. At least he will have the double satisfaction of revenge and being put out of his misery afterwards by his mechanized jailor. Despite his efforts to temporarily separate himself from his constant attendant, the tenacious Fury still manages to prevent Danner from being able to kill again: that is, to murder Hartz. But Hartz does succeed in simultaneously killing Danner, just at moment the Fury foils his vindictive charge.

It is then that Hartz seeks to escape the same fate that befell the man of whom he made a dupe in his ruthless career designs. The very hacking code that he promised to use to deliver Danner from his sentence does indeed now save Hartz from sharing the doom of his morally clueless sap, the late Danner. However, the seemingly ruthless Hartz has by this point finally evolved just enough inwardly to have developed the fundamentals of a natural human conscience. At the end of the story, we come full circle, for we have the re-emergence in the mind of Hartz of the very psychological triggers that underlie the metaphorical construct of the Fury in Ancient Greek mythology. Thus the animated-metal symbol and imposer of afflicted guilt has been found disposable sooner than predicted. The flip side of Hartz (which is a nascent conscience) need not worry now over his cybernetic corruption of automated justice and its technological ramifications. If he is the first, he will not be the last to be pursued by the wholly mental-emotional construct of guilt -- now newly reinvented in him. He hears the footfalls of his Fury (a leitmotif in throughout the story), but there is no exterior robot to sound them. They fall within the silence of his mind alone. While this story may have been written fifty-seven years ago when the world still fundamentally operated by means of a clerk manipulating a filing cabinet, it feels intensely relevant and prophetic for the times in which we now live.

This tale may now be most readily obtained in this recent collection: The Last Mimzy: Stories, by Henry Kuttner, Del Rey Books, Copyright 2007.

This may sound familiar, but in Kuttner's hands it has a different outcome than the typical science-fictional trope. In exchange for peace and stability, which the objective dispassionate synthetic mind of centralized planet-spanning computers can provide without error, humanity gives up self-governance. The computerized and wholly mechanized world supplies psychological satisfaction through virtual reality experiences transmitted by artificially induced trance states. All necessities are artificially manufactured and delivered as needed. Human society atomizes, as people become self-engrossed in personal whims and selfish pleasures. Machines exist only for humankind's physical health and egoistic pleasure. The moral compass of society loses its orientation as the need for struggle, competition, social discourse, human cooperation and emotional connection dissolve before computerized illusions of hedonistic and imaginative fulfillment. For this story, all this is already history. The author introduces us to a society that has just barely managed a slim generation ago to pull itself out of social implosion, by reasserting an active role in the material world. Human beings were failing to reproduce, because the underpinning social structures for basic human bonding had nearly entirely disintegrated. Faced with self-extinction, individuals came together to redirect the comprehensively mechanized-computerized world with a new fundamental program: enable human beings to become socially responsible again.

What these pioneers at rebuilding the mental construct of society face, however, is daunting: "conscience" itself has to be not merely re-learned but re-invented. The super-ego has to be reactivated. So in addition to dismantling technologies that provided for every comfort, pleasure and imaginative whim (so that human beings would be motivated to form social connections again with their fellows), negative reinforcement has to be introduced into a newly activated society that has been for so long in a technological womb of passivity. Here, Kuttner cleverly reinvents the mythological concept of the Fury in terms of a technological (and robotic) force of social control.

At this stage in the redevelopment of human society, people, while intellectually advanced, are still so morally infantile that murder is the essential form of moral corruption as people become re-accustomed to interacting with one another in complex ways. The title of the story is taken from a cryptic verse by Milton, who envisions that figure from Greek myth, the Fury, as a "two-handed engine at the door": the pursuing conscience of the person who mistakenly thinks he or she can escape the psychological implications of taking the life of another. In Kuttner's story, the Furies are robots that track down and follow those who have committed murder. The world is under pervasive sensory surveillance by a vast computer-mind maintained by a hierarchical human bureaucracy. An act of murder is inevitably discovered, and the perpetrator identified by the source of law and order: the wholly objective engine of artificial intelligence. The murderer then receives his or her Fury, a faceless, voiceless robot that follows them wherever they go, and keeps a vigil over them wherever they stay or rest.

These special robots will prevent their inmates from harming again, and at a carefully calculated moment, dependent on unknown factors of the individual, the Fury will execute the felon by any manner of assorted methods. The robotic Fury does not (and needs not) hinder the movement of its ward. This Fury of mechanical body can make of the entire world a prison for its charge, for the murderer can neither destroy it nor elude it. Its tenacious but serene accompaniment of its assigned felon is an example to all who observe the bizarre pair of the cost of taking the life of another: an act of harm, as the author points out, that cannot be practically undone.

In the story at hand, the supporting character, Hartz, a high-ranking administrator, induces a maladjusted citizen, Danner, into committing an act of murder, by demonstrating that he has the mathematical programming ability to undermine the normally unerring directives of the master-computer to impose the tenacious Furies upon guilty members of society. Hartz is a complex figure, despite not being the central character, for he believes in the moral rehabilitation of humankind so that it might not regress and lose its will to achieve character and reproduce itself. However, he is frustrated in being the penultimate controller. Hartz wants to be the master controller in this new alliance with the more perfect computerized/mechanized coordinators of human civilization. He still retains the regressed impatience of the id needing immediate gratification, and so, for all his sophistication of responsibility, he has not the restraint of desire found in a fully evolved human consciousness. The man above him, in short, is a mere hindrance, rather than a respected superior partner (in short, a recognized fellow human being) in the new project to rehabilitate humankind.

In the central character of Danner, Hartz sees a man even less evolved than himself, who can be persuaded to commit the very act that the institution to which Hartz belongs seeks most primarily to correct. As for Danner, he belongs to the last generation to enjoy the previous era of no psychological or physical challenges, and he lived long enough in that former reality to have it deeply imprinted on him. Thus Danner is incapable of fully embracing or finding higher satisfaction in the new reality, which requires effort and puts character-building limits on the boons of existence. Danner is deceived into believing that Hartz will use his hacking ability to derange the moral directives of the master computer, but Hartz knows that if he acts upon his knowledge, he will create a fault that may unravel the whole system of social control and thus humankind's general rehabilitation.

Despite his selfish ambitions, Hartz ironically has evolved enough to recognize that if he allows his faulty super-ego to have its way too far, it will ultimately defeat the purpose of the whole philosophical revolution to put a socially-responsible humanity back on its feet. So Danner ends up with a Fury as his constant silent companion, until the unknowable date when the robot will receive the algorithmic command from the central computer to destroy Danner. Yet Danner never succeeds in acquiring an inward sense of moral guilt, only an outraged resentment that his master-conspirator has somehow failed to protect him from the very fate that he had been guaranteed not to suffer. In return, he has gotten the promised unlimited source of wealth with which to pursue the pleasures Danner once knew in his youth before such things became rationed and contingent upon personal effort and social success. But where is the satisfaction when one is condemned to a mobile (though invisible) spot on Death Row?

Danner ultimately descends into murderous madness, as his unshakable Fury makes him an outcast even when his fellow human beings are willing to share his company, for his ubiquitous warden makes him attractive only to those who connect with him because of their superficial fascination with his impending doom. In the end, Danner seeks to slay Hartz, who can no longer put him off with promises to discover the reason for his failure to scramble the code of computerized justice and allow his minion to escape his punishment. At least he will have the double satisfaction of revenge and being put out of his misery afterwards by his mechanized jailor. Despite his efforts to temporarily separate himself from his constant attendant, the tenacious Fury still manages to prevent Danner from being able to kill again: that is, to murder Hartz. But Hartz does succeed in simultaneously killing Danner, just at moment the Fury foils his vindictive charge.

It is then that Hartz seeks to escape the same fate that befell the man of whom he made a dupe in his ruthless career designs. The very hacking code that he promised to use to deliver Danner from his sentence does indeed now save Hartz from sharing the doom of his morally clueless sap, the late Danner. However, the seemingly ruthless Hartz has by this point finally evolved just enough inwardly to have developed the fundamentals of a natural human conscience. At the end of the story, we come full circle, for we have the re-emergence in the mind of Hartz of the very psychological triggers that underlie the metaphorical construct of the Fury in Ancient Greek mythology. Thus the animated-metal symbol and imposer of afflicted guilt has been found disposable sooner than predicted. The flip side of Hartz (which is a nascent conscience) need not worry now over his cybernetic corruption of automated justice and its technological ramifications. If he is the first, he will not be the last to be pursued by the wholly mental-emotional construct of guilt -- now newly reinvented in him. He hears the footfalls of his Fury (a leitmotif in throughout the story), but there is no exterior robot to sound them. They fall within the silence of his mind alone. While this story may have been written fifty-seven years ago when the world still fundamentally operated by means of a clerk manipulating a filing cabinet, it feels intensely relevant and prophetic for the times in which we now live.

This tale may now be most readily obtained in this recent collection: The Last Mimzy: Stories, by Henry Kuttner, Del Rey Books, Copyright 2007.

Friday, March 16, 2012

Review: "The Woods-Devil" by Paul Annixter

Originally published as a short story in February 1948 issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine, when it was still a sophisticated periodical like Harper's rather than a young woman's interest magazine like Glamour, this is a tale that has haunted me ever since I read it as a freshman in high school back in 1983 in a literary scholastic anthology. It was written under the pseudonym, "Paul Annixter", actually by Howard Allison Sturtzel, and later published ten years later in an anthology collection of short stories entitled, Devil of the Woods: A Collection of Thirteen Animal Stories, as by Paul Annixter, printed by Ayer Publishing Company in 1958. While accessible and of interest to the adolescent mind concerned with the emerging consciousness of newly adult concepts of self-reliance, this story follows the naturalistic school of literature that grew out of the school of realism, fully crystallizing its own distinct form from the late 19th century through the early 20th century. Naturalistic writing is popularly exemplified by Jack London, Joseph Conrad and Stephen Crane. This school of literature sought to make use of the new discoveries of natural science to extrapolate through fiction the animal nature of humankind buried beneath what was perceived to be a veneer of civilized sophistication, moral culture and artificially-conditioned social courtesy. Naturalist fiction writers sought to create imaginative scenarios where our artificial training to be civilized and philosophically composed met the naked test of the ultimate needs of survival or severe conditions of environmentally-induced psychological stress. In "The Woods-Devil" , the adolescent character, Nathan, living in the North Woods of Maine, must alone face the rigors and dangers of the wilderness in winter to sustain the now strained livelihood of his family's lonely homestead, because his widower father is laid up by physical injury. In the depths of an isolated world where survival hangs by a thread, he must face the "woods-devil", a creature his father has warned him of, and which is in fact a wolverine. What is so powerful about this tale is that the author has a narratively unobtrusive scientific understanding of the environment and the dangerous animal to which the young man is pitted, but he combines this with the perceptions of a non-scientific point of view, and the immediacy of experience and oral tradition of understanding to which simple homesteaders (and a boy a no less) are inescapably subject. Here we experience the tension of frightening folklore that is nonetheless based upon the practical edge of survival to which lonely inhabitants were subject in the Maine woods before the arrival of electricity and the broadened perspective and amenities brought by modern transportation. The central character Nathan, finds himself forced to assume an adult role because his father, the only provider remaining in his life, incapacitated by what the boy discovers is the psychologically discomforting revelation of physical vulnerability in his otherwise stoutly capable parent. He must now of necessity fetch the animals caught in the traps set by his father, so that they might have the income to see them through the winter. But there is a competitor for the victims of those traps: the woods-devil. While we may later learn that it is a once common creature of the North American ecosystem related to the badger, commonly called the wolverine, which the American Indians called the "skunk bear" for its stench of musk, ferocity of nature and dangerous proclivities, the author in this story drives us to understand this beast in terms of how a person on the ground with no scientific perspective was forced to cope with such an animal. There is the comfort of knowledge and the remove from untamed nature in which most of us have existed for over eighty years. The author vividly forces us to inhabit only the reality the young adolescent Nathan must face in the sylvan desert of this story. It would not even matter if he had had access to our scientific works of reference. Any such blandly empirical knowledge would not mitigate the danger he faces in his lonely journey to check the series of traps set by his father in the hunger of winter's wasteland. The boy has no contraptions to protect himself from this animal in the starving madness of winter's depths. The wolverine is an intelligent animal that cunningly and aggressively seizes the opportunities provided by humankind's snares of its natural quarry. Nathan is forced to compete with a creature, which for all intents and purposes, has a numinous effect on his psyche and exercises a very material threat to his physical wholeness and continuance. The young man must discipline not only his childish fears, but also the very real practical threat that even a full-grown man must face in his trek through the snow-bound wilderness of America's northernmost state. When I read this of an age level with the main character, I palpably felt his fear, his psychological tension, his willful determination, his inaugural sense of real vulnerability being risked for the sake of the survival of his household. One cannot exaggerate the skill with which Annixter puts the reader in the cockpit of this story's naturalistic sense of Nathan trying to balance his fight-or-flight instincts with a singular determination of mind to survive (and simultaneously help save the remnant of his family), and this without recourse to any form of help from a broader human community. When I read this as a newly-emergent teenager, I needed to cross no literary hurdle to identify with and be absorbed by the words of this tale. It was a story that I consumed as naturally as air and water, and it has left me pondering the nature of the human pioneer in the face of nature's less kindly side. Nathan's tenuous hold on survival by hiding in a hollow log when he at last crosses paths with the forewarned creature of hellish nature is an image burned in my mind as deeply as any actual experience I underwent in the real life I have since lived. Wolverines may be a merely a curiously irascible creature that we may watch and bemusedly learn about within the safety of our living rooms as the subject of a documentary on some educational cable channel, but Annixter reconstructed the intimidating and superstitious aura this animal must have once exercised upon the human psyche, when isolated settlers had no other resource than their bare wits and the practical wisdom of intimate experience.

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

Review: "The Black Gondolier" by Fritz Leiber, Jr.

Originally written for the weird story collection, Over the Edge, published in 1964 and edited by August Derleth for the famous specialty small press, Arkham Press, this twenty-eight-page novelette shows Fritz Leiber at the peak of his mature writing powers in the High Sixties. It is a contemporary dark science-fantasy so prescient as to make it particularly creepy in this present era in which we live, where our addiction to fossil fuels now pounds the drumbeat of doom daily in our ears as climate change encroaches more and more deeply into our lives. Here we encounter the one-two-punch double mastery of Leiber, who wielded comfortably the thought patterns of both science fiction and weird fiction, in this story hypnotically, eerily (and inextricably) interconnected to its premise, unfolding mystery, ramifications and implications.

But is more than that. It is the human psyche: where does its incredible and incomparable power of deduction end and its seduction and potential fallibility in the realm of imagination and schizophrenia begin? How does a sympathetic person who knows the world is not all that it seems help and understand a friend, whose rare form of intelligence and perspicacity alienate him from the world of appearances. In this story, one main character, the first person voice of the narrative, must constantly reconsider his assessments of his troubled friend: is he mad? is he in danger? does he speak truth? does he merely describe hallucinations and unfounded suspicions, which will nevertheless drive him to self-destruction? The other main character is a man most might write off as an eccentric slum-tenant of the ecological ghetto of Venice, California. His morbid obsession with modern humankind's mono-minded reliance upon petroleum has led him to believe in the parallel existence of an evil sentience with a cosmic agenda. Here is a tale set in the dregs of America's now faded oil boom.

Here is a story that posits a collective intelligence of a non-biological kind inherent in a substance that effectively controls the fate of humankind as much at the time in which the story was written as it does now. The numinous power of oil has taken hold of the minds of men far more insidiously than the venerable madness for gold. It had waited, biding its time for our technology to properly harness it, while occasionally surged to the surface and caught mysterious fire in the oily swamps of Antiquity. Here a person finally perceives its pernicious, insidious influence, and the source of that power begins to understand that it is being consciously perceived. It is a story of the discoverer becoming the hunted by that which he has laid bare in the disturbed light of his unusual mind. In between the two entities is a sympathetic person who still clings to the world to which we the readers belong, but who increasingly finds himself persuaded by the underlying reality fitfully described by his troubled friend. The man in between must decide how he is to save his friend and from what. Is it merely his friend's mental health that is at stake or his very life? Is the threat a figment of his mind inspired by the polluted environment in which he lives, or is it something wholly exterior, intangible to the established theories of science and psychology, but no less real and threatening for all that?

Oh, yes, like so much else by Leiber, this is a tale of mystery, as much as a story of increasing horror and weirdness. It is also a conversation where science itself is challenged for its assumptions in more than a fanciful way. Here is philosophical insight we can take away with us and mull over with fascination and inner turmoil. But the imminent shape of menace itself in this story -- the so-called, Black Gondolier -- we are left to wonder about: is it a physical manifestation of a powerful psychological projection, like a Buddhist tulpa, or is it a specifically purposeful animation of a seemingly inanimate constituent, responding articulately (and in a symbolically and anciently appropriate form) to the threat of discovery by a sapient human consciousness? Please find this story in the recent anthology of short weird fiction, The Black Gondolier, by Fritz Leiber; edited by John Pelan and Steve Savile; published by E-Reads Publications, New York, NY; copyright 2003.

But is more than that. It is the human psyche: where does its incredible and incomparable power of deduction end and its seduction and potential fallibility in the realm of imagination and schizophrenia begin? How does a sympathetic person who knows the world is not all that it seems help and understand a friend, whose rare form of intelligence and perspicacity alienate him from the world of appearances. In this story, one main character, the first person voice of the narrative, must constantly reconsider his assessments of his troubled friend: is he mad? is he in danger? does he speak truth? does he merely describe hallucinations and unfounded suspicions, which will nevertheless drive him to self-destruction? The other main character is a man most might write off as an eccentric slum-tenant of the ecological ghetto of Venice, California. His morbid obsession with modern humankind's mono-minded reliance upon petroleum has led him to believe in the parallel existence of an evil sentience with a cosmic agenda. Here is a tale set in the dregs of America's now faded oil boom.

Here is a story that posits a collective intelligence of a non-biological kind inherent in a substance that effectively controls the fate of humankind as much at the time in which the story was written as it does now. The numinous power of oil has taken hold of the minds of men far more insidiously than the venerable madness for gold. It had waited, biding its time for our technology to properly harness it, while occasionally surged to the surface and caught mysterious fire in the oily swamps of Antiquity. Here a person finally perceives its pernicious, insidious influence, and the source of that power begins to understand that it is being consciously perceived. It is a story of the discoverer becoming the hunted by that which he has laid bare in the disturbed light of his unusual mind. In between the two entities is a sympathetic person who still clings to the world to which we the readers belong, but who increasingly finds himself persuaded by the underlying reality fitfully described by his troubled friend. The man in between must decide how he is to save his friend and from what. Is it merely his friend's mental health that is at stake or his very life? Is the threat a figment of his mind inspired by the polluted environment in which he lives, or is it something wholly exterior, intangible to the established theories of science and psychology, but no less real and threatening for all that?

Oh, yes, like so much else by Leiber, this is a tale of mystery, as much as a story of increasing horror and weirdness. It is also a conversation where science itself is challenged for its assumptions in more than a fanciful way. Here is philosophical insight we can take away with us and mull over with fascination and inner turmoil. But the imminent shape of menace itself in this story -- the so-called, Black Gondolier -- we are left to wonder about: is it a physical manifestation of a powerful psychological projection, like a Buddhist tulpa, or is it a specifically purposeful animation of a seemingly inanimate constituent, responding articulately (and in a symbolically and anciently appropriate form) to the threat of discovery by a sapient human consciousness? Please find this story in the recent anthology of short weird fiction, The Black Gondolier, by Fritz Leiber; edited by John Pelan and Steve Savile; published by E-Reads Publications, New York, NY; copyright 2003.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Review: "Smoke Ghost" by Fritz Leiber, Jr.

This 15-page short story originally appeared in the October 1941 issue of Unknown Worlds. The author, Fritz Leiber, had just a few years before entered his first phase of greatness as a writer, especially as a fantasiste, but this piece is an example of his early mastery of the weird fiction form. In the mid-1930s he had corresponded with H.P. Lovecraft. Then Leiber showed himself to be a budding writer, articulating his appreciation of an established master, seeking advice on developing manuscripts, and learning from the veteran author what he needed to perfect his own natural brand of emerging talent. By the early 1940s, we encounter in Leiber a writer who has fully acquired stylistic finesse, dramatic power, and deftly-handled symbolic details; "Smoke Ghost" exemplifies these qualities, and takes the reader by astounding surprise in how it conjures up a true sense of terror. In the world of fantasy, Leiber is a writer who can take you into the deepest wells of laughter, suspense, thrills, and even compassion, and always these sensations hit you unexpectedly. These are the fruits of a complex weaver of plot and character. This was how the reviewer mostly knew Mr. Leiber's work, as most of his dark fantasy/weird fiction was not easy to obtain or as highly touted for a number of years. But once one discovers this other side to Leiber's imagination, it comes as a revelation. If he could make you laugh at the heroic gusto, knowing foolishness. and playful wits of his famous duo of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, his darker tales can scare you out of your wits, and he does in no way use gross psychotic violence to achieve this. No, Leiber is a master of psychological subtlety and depth, and when he employs this perspective on what causes unease and mind-fracturing mystification, he frighteningly exposes the scientific loose ends raggedly veiled by our insistently bland, Modernistic, prescriptive understanding of the cosmos. Here he can work a fear into the reader like no other, and Leiber never wastes a word in the particular magic, dark or otherwise, that he unerringly creates. His prose always comes across as a musical composition in terms of the well-wrought explication of the story, and his infallible dialogue could always be directly lifted into a movie script. "Smoke Ghost" visits upon us the awesome and insoluble inward nature of a ghostly phenomenon within a prosaic urban setting, replete with drab office building, an ever-reliable elevated commuter train, a successful businessman with an unresolved childhood, and a well-meaning literal-minded secretary who is fodder for the insidious forces underlying our brashly confident artificial world. The antagonist in this story emerges slowly, marginally, minimally, crudely materially at first, and then stalks our protagonist with growing pervasiveness, intrusiveness, and ironically, increasing indefinability. The ghost here is more a life-form stemming from another wave-length to our fleshly zone, yet it cohabits our world, manifesting gradually through the niggling detritus of our urban existence, seeking entry, attachment and energy through the doubts that increasingly crowd our minds as life progresses, no matter how hard we try to contain them, rationalize them, and shunt them away. Leiber's ghost is and remains of uncertain nature, something god-like, something demonic, something perhaps spawned from racial memory itself. It is a genius loci of a monstrous sort, though predatorially sly, alienatingly insistent and ultimately unforestallable, despite the employment of every resource of human cunning and survivalism. And yet, in the end, it can be appeased, and the manner of that seems to come from the deepest instincts of the human psyche -- ones we feel we have outgrown or else forgotten, but in the moment of ultimate terror, can summon up as a survival reflex encoded in our nervous system from days of flint-tipped spear and lightning-gifted fire. The story may most readily be acquired today from the collection, Selected Stories by Fritz Leiber, published by Night Shade Books, copyright 2010.

Monday, January 10, 2011

In Defense of "Older" and "Genre" Fiction

Of course, the primary purpose of this blog is to highlight the power and enjoyability of short fiction, establishing how its literary effectiveness is on a par with the novel, which in today's creative output is fast eclipsing its sister form. This blog has also emphasized speculative and imaginative fiction over mainstream fiction, not because it does not recognize the validity of the latter, but to remedy a false perception. In America, that which gets defined as "genre" rather than "literary" is actually often as intellectually and morally stimulating as that which the establishment defines as "true literary art". This blog seeks to inspire an interest for good "genre" fiction among those who have been taught to ignore it or to have an uninformed prejudice against it. The problem with the definition of "genre" is that it implies limited scope, superficiality and childish artificiality. Yet there is bestselling, critically-vaunted mainstream fiction that exudes these very contemptible qualities beneath a veneer of gritty sophistication, and there is fiction pinned with the shining medal of "literary" which fails to come close to the profundity of insight found in much fiction branded with the admonitory scarlet phrase "genre".

Now it will also be noticed that much of the short fiction presented here dates from over half a century ago. Part of this emphasis is again an attempt to rectify another imbalance, because the media always tends to favor the more recent. Short fiction flourished at that time, and that was where many authors were making their most important artistic statements, even if later, when novels became more important, they might rework those original succinct literary statements into long fiction forms. Much short fiction written after novels became the preferred reading format merely served as a way for an author to make a stylistic splash for notoriety's sake, while he or she otherwise saved his or her best storytelling ideas for the novel (where the real money now was). This is not to say there were not good short stories written in later eras; it is only to say that before that, when periodical fiction was preferred by the consumer, there was relatively more good fiction to be found in the shorter format. In those days you could read a short story from a magazine you bought at a drugstore, and find yourself looking out the window afterward, sighing with wonder, while you appreciated how the author had given you a new wrinkle in your philosophical outlook on life.

So having established these "underdog" justifications, I will now seek to address frequently voiced prejudices heard today on the internet against "older fiction", and show (again from an underdog perspective) why fiction from the peak era of twentieth century culture (or even of the nineteenth century) is still a worthwhile, enjoyable and even essential source of reading for the twenty-first century reader. The most frequent complaints I run across are: "naive", "idealistic", "simplistic", or even "quaint". What I have seen these criticisms applied to makes me wonder if the reader understands English. And then I consider what must be their normal diet of reading: what dominates contemporary fiction and graphic novels? Today, it doesn't matter if we're talking about literary, mainstream, comic books, or contemporary science fiction, mysteries, horror and fantasy, much of it has now fully embraced the flagrant culture of unashamed cynicism. Sexuality is all about maneuvers of power not love or tender affection. The quest is all about power not understanding. Violence is celebrated with artfully sadistic descriptions. Unsolvable dysfunctionality among the characters is proffered as an acceptable norm. Relationships are about relative advantage for selfish purposes. The heroes and the villains are indistinguishable, and their is no narrative voice decrying this. Women and men may be portrayed as equals in a technical sense, but women suffer awful violence and the men do not seem to have much more compassion than a "tough luck, babe" attitude, and no one troubles themselves overmuch in remedying the source of the problem except to enact revenge. In fact male characters suffer violence too and accept it like rain falling on their head. Violence always trumps any niceties of enlightened understanding or opportunity for higher purpose. The protagonists fight for what they want within the bounds of evil rules which are accepted as though they are laws of nature. As far as story-lines go, there are often chaotic shifts in point of view, gratuitous scenes that serve no purpose, hacked up plot-lines, and some form of violence is always the solution to the problem. No effort is made to rise above the traumatized psyche, but only to laughingly (if bitterly) accept such fractured states of being as supporting the sort of advantageously-damaged mind necessary to negotiate a world where everyone is out for themselves and conscience and scruples are for the losers. This, my friends, is the fiction of a doomed culture.

So if you want an alternative to stewing in the sickness of the moment, and realize you have a healthy respect for hope, conscience, expanding understanding, moral enlightenment and developing a higher consciousness of the miracle that is our cosmos, keep reading this blog to discover writers and writings that support this attitude of being. We have not degenerated as human beings, only that which is proffered as cutting edge literature has. Let us read again those who wrote about tackling the riddles and the problems of our existence and sought liberating truth and growth of compassion. What distinguishes these authors is their desire not to accept bland justifications for or explanations of things as they are (or to blindly accept the version of reality the cultural media encourages us to accept), but to question the validity of any permutation in our existence which seems to raise questions of moral consciousness, especially if we are expected to take it for granted. You will find that the best of these authors accomplish this through psychological subtlety, mutually broadening perspectives between interacting characters, courageous and skillful imagination, and some even employ a knowing humor that challenges the sturdiness of any new perspective adapted in the story. These authors are not moralizers. They are searching for answers that are not easy to obtain and sometimes have unpleasant or humbling implications. They do not make claims for the truth but they seek to find its direction. They do not preach, but their stories entice the engaged mind of the reader to include itself on the philosophical quests on which they drive their characters.

Now it will also be noticed that much of the short fiction presented here dates from over half a century ago. Part of this emphasis is again an attempt to rectify another imbalance, because the media always tends to favor the more recent. Short fiction flourished at that time, and that was where many authors were making their most important artistic statements, even if later, when novels became more important, they might rework those original succinct literary statements into long fiction forms. Much short fiction written after novels became the preferred reading format merely served as a way for an author to make a stylistic splash for notoriety's sake, while he or she otherwise saved his or her best storytelling ideas for the novel (where the real money now was). This is not to say there were not good short stories written in later eras; it is only to say that before that, when periodical fiction was preferred by the consumer, there was relatively more good fiction to be found in the shorter format. In those days you could read a short story from a magazine you bought at a drugstore, and find yourself looking out the window afterward, sighing with wonder, while you appreciated how the author had given you a new wrinkle in your philosophical outlook on life.

So having established these "underdog" justifications, I will now seek to address frequently voiced prejudices heard today on the internet against "older fiction", and show (again from an underdog perspective) why fiction from the peak era of twentieth century culture (or even of the nineteenth century) is still a worthwhile, enjoyable and even essential source of reading for the twenty-first century reader. The most frequent complaints I run across are: "naive", "idealistic", "simplistic", or even "quaint". What I have seen these criticisms applied to makes me wonder if the reader understands English. And then I consider what must be their normal diet of reading: what dominates contemporary fiction and graphic novels? Today, it doesn't matter if we're talking about literary, mainstream, comic books, or contemporary science fiction, mysteries, horror and fantasy, much of it has now fully embraced the flagrant culture of unashamed cynicism. Sexuality is all about maneuvers of power not love or tender affection. The quest is all about power not understanding. Violence is celebrated with artfully sadistic descriptions. Unsolvable dysfunctionality among the characters is proffered as an acceptable norm. Relationships are about relative advantage for selfish purposes. The heroes and the villains are indistinguishable, and their is no narrative voice decrying this. Women and men may be portrayed as equals in a technical sense, but women suffer awful violence and the men do not seem to have much more compassion than a "tough luck, babe" attitude, and no one troubles themselves overmuch in remedying the source of the problem except to enact revenge. In fact male characters suffer violence too and accept it like rain falling on their head. Violence always trumps any niceties of enlightened understanding or opportunity for higher purpose. The protagonists fight for what they want within the bounds of evil rules which are accepted as though they are laws of nature. As far as story-lines go, there are often chaotic shifts in point of view, gratuitous scenes that serve no purpose, hacked up plot-lines, and some form of violence is always the solution to the problem. No effort is made to rise above the traumatized psyche, but only to laughingly (if bitterly) accept such fractured states of being as supporting the sort of advantageously-damaged mind necessary to negotiate a world where everyone is out for themselves and conscience and scruples are for the losers. This, my friends, is the fiction of a doomed culture.

So if you want an alternative to stewing in the sickness of the moment, and realize you have a healthy respect for hope, conscience, expanding understanding, moral enlightenment and developing a higher consciousness of the miracle that is our cosmos, keep reading this blog to discover writers and writings that support this attitude of being. We have not degenerated as human beings, only that which is proffered as cutting edge literature has. Let us read again those who wrote about tackling the riddles and the problems of our existence and sought liberating truth and growth of compassion. What distinguishes these authors is their desire not to accept bland justifications for or explanations of things as they are (or to blindly accept the version of reality the cultural media encourages us to accept), but to question the validity of any permutation in our existence which seems to raise questions of moral consciousness, especially if we are expected to take it for granted. You will find that the best of these authors accomplish this through psychological subtlety, mutually broadening perspectives between interacting characters, courageous and skillful imagination, and some even employ a knowing humor that challenges the sturdiness of any new perspective adapted in the story. These authors are not moralizers. They are searching for answers that are not easy to obtain and sometimes have unpleasant or humbling implications. They do not make claims for the truth but they seek to find its direction. They do not preach, but their stories entice the engaged mind of the reader to include itself on the philosophical quests on which they drive their characters.

Sunday, April 25, 2010

Review: "Shark Ship" by Cyril Kornbluth

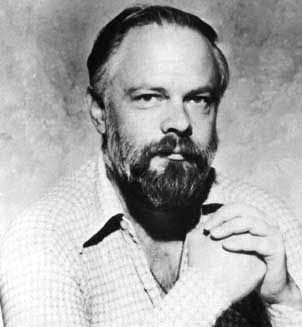

This short story of thirty pages had its inaugural publication in 1958 under the title, "Reap the Dark Tide", but reverted to the author's original title when it was released in a posthumous collection of his works the following year. The year it first saw print was also the year Kornbluth died, and in 1959 was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Novelette. If there is any evidence that Kornbluth would have become a major author in his own right during the New Wave movement of the 1960s, this is a prime specimen. He, like Philip K. Dick and Alfie Bester were '50s writers ahead of the curve, but Kornbluth's untimely death prevented the full realization of the promise found in his short fiction and his collaborative novels with Frederick Pohl. It cannot be doubted that the 1960s would have brought his creative genius to full fruition, due to the truly expansive editorial and imaginative parameters set by that boundary-pushing decade of intellectual ferment. This particular story finds him in exceptional form, and shows he died at a time when his writing was attaining a new level of ambition. What we have in this tale of deceptively simple yet subtly ironic title, is a work that could have been turned into an epic science fiction novel. His research into nautical engineering, meteorology, oceanic currents, marine ecosystems, population control dynamics, and sociopolitical organization is pieced together in brilliant narrative form, and his extrapolations therefrom into a future, self-sufficient, sea-bound, human society conveys intense plausibility. For such a society to exist wholly independent of land resources, he paints a culture of hyper-organization as ruthlessly efficient as an ant colony, constantly following the algal blooms that spawn the greatest harvests of the world's seas. Maintenance of one's means of survival is paramount, since these groups may never return to land to obtain replacements. It is war of watchfulness, industrial scale recycling and meticulous brigade-form policing against oxidation. Every member of society performs a task intrinsic to the success of the whole. Kornbluth eschews the temptation to paint a dystopian one among these marine-bound humans, who have an equally strong sense of humanity tempering their iron-willed commitment to sacrifice for the greater good when necessity demands it. Their government is a representational democracy, bound by legal limits based on purely practical considerations. His world-building in terms of these seafaring folk paints a noble and convincing picture of collective ingenuity and service over self. This is not to say there is not a dystopian presence in this tale of a future Earth of riven populations. It is the world of land-dwelling humans, which has become an utter mystery to those descendants of the humans who generations ago volunteered to alleviate population pressure by voluntary exile to the sea. One of the ships in one of several tribal fleets suffers the fatal mishap of losing its net in a sudden squall, though the captain does succeed in preventing the ship from capsizing. There are no spare fibers from the rest of their parent fleet from which they might make another. Though they freshly retain their share of a great marine harvest that may feed them for several months yet, they will never be able to participate again in such ventures. After being abandoned by the rest of the fleet as a matter of their ancient code of collective survival, they choose (rather than opting for the traditional mass suicide to avert the ultimate resort of cannibalism) to reconnoiter a navigable place of land to seek material to make a new net. Such a decision is tantamount to breaking an age-old agreement with the land-dwellers against making any such move as an act of trespass in spheres now determined to be mutually inviolable. The scout team discovers that the landed side of humanity, though it was the fount of the civilization from which their own sea-going one sprang, has become something very odd indeed. Just as the sea people developed a highly disciplined and honor-bound culture over the generations to cope with the harsh rules of the sea and the requirement to be totally self-sufficient, the land people had developed their own means of coping with the problem of overpopulation and limited land resources. I will not reveal the terrible truth, but suffice to say, it rests with this single transgressive ship to take the lead in saving the idea of humanity and creating therefrom a viable civilization for the future of the planet. What haunts the mind is the prophetic quality in Kornbluth's revelation of the landward half of humanity. Many aspects of today's popular media culture are pointing in the direction he reveals in the evolutionary psychology of the land-bound folk. Where cooperative solutions fail, where does increasingly desperate competition for resources lead the collective mind of a society originally disposed toward mercy but which atavistically views such a humane disposition as a maddening burden? As with all my Kornbluth recommendations I point you to the following volume put out by the commendable efforts of the New England Science Fiction Association: His Share of Glory. Written by C. M. Kornbluth. Published by NESFA Press. Copyright 1997.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)