Wednesday, October 12, 2011

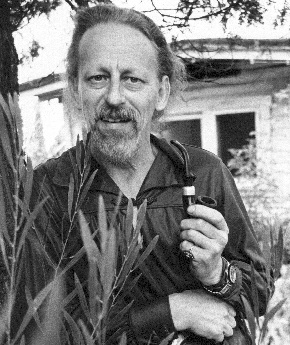

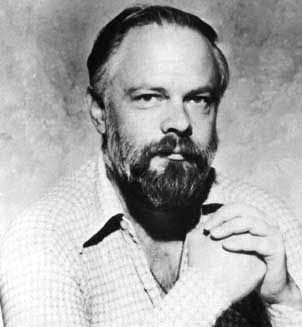

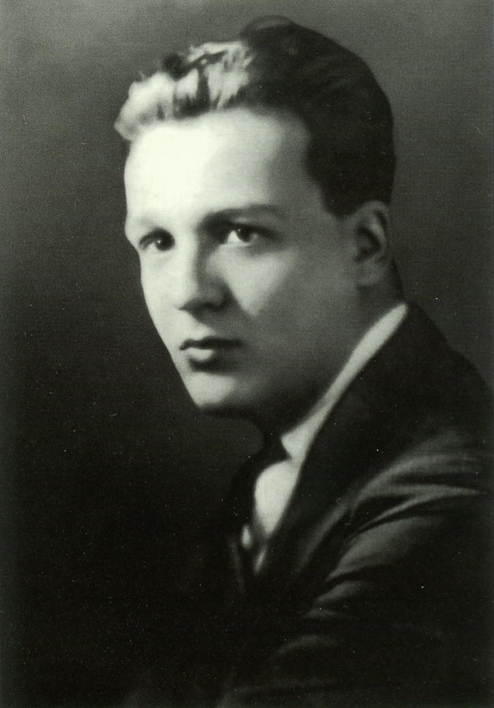

Review: "Smoke Ghost" by Fritz Leiber, Jr.

This 15-page short story originally appeared in the October 1941 issue of Unknown Worlds. The author, Fritz Leiber, had just a few years before entered his first phase of greatness as a writer, especially as a fantasiste, but this piece is an example of his early mastery of the weird fiction form. In the mid-1930s he had corresponded with H.P. Lovecraft. Then Leiber showed himself to be a budding writer, articulating his appreciation of an established master, seeking advice on developing manuscripts, and learning from the veteran author what he needed to perfect his own natural brand of emerging talent. By the early 1940s, we encounter in Leiber a writer who has fully acquired stylistic finesse, dramatic power, and deftly-handled symbolic details; "Smoke Ghost" exemplifies these qualities, and takes the reader by astounding surprise in how it conjures up a true sense of terror. In the world of fantasy, Leiber is a writer who can take you into the deepest wells of laughter, suspense, thrills, and even compassion, and always these sensations hit you unexpectedly. These are the fruits of a complex weaver of plot and character. This was how the reviewer mostly knew Mr. Leiber's work, as most of his dark fantasy/weird fiction was not easy to obtain or as highly touted for a number of years. But once one discovers this other side to Leiber's imagination, it comes as a revelation. If he could make you laugh at the heroic gusto, knowing foolishness. and playful wits of his famous duo of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, his darker tales can scare you out of your wits, and he does in no way use gross psychotic violence to achieve this. No, Leiber is a master of psychological subtlety and depth, and when he employs this perspective on what causes unease and mind-fracturing mystification, he frighteningly exposes the scientific loose ends raggedly veiled by our insistently bland, Modernistic, prescriptive understanding of the cosmos. Here he can work a fear into the reader like no other, and Leiber never wastes a word in the particular magic, dark or otherwise, that he unerringly creates. His prose always comes across as a musical composition in terms of the well-wrought explication of the story, and his infallible dialogue could always be directly lifted into a movie script. "Smoke Ghost" visits upon us the awesome and insoluble inward nature of a ghostly phenomenon within a prosaic urban setting, replete with drab office building, an ever-reliable elevated commuter train, a successful businessman with an unresolved childhood, and a well-meaning literal-minded secretary who is fodder for the insidious forces underlying our brashly confident artificial world. The antagonist in this story emerges slowly, marginally, minimally, crudely materially at first, and then stalks our protagonist with growing pervasiveness, intrusiveness, and ironically, increasing indefinability. The ghost here is more a life-form stemming from another wave-length to our fleshly zone, yet it cohabits our world, manifesting gradually through the niggling detritus of our urban existence, seeking entry, attachment and energy through the doubts that increasingly crowd our minds as life progresses, no matter how hard we try to contain them, rationalize them, and shunt them away. Leiber's ghost is and remains of uncertain nature, something god-like, something demonic, something perhaps spawned from racial memory itself. It is a genius loci of a monstrous sort, though predatorially sly, alienatingly insistent and ultimately unforestallable, despite the employment of every resource of human cunning and survivalism. And yet, in the end, it can be appeased, and the manner of that seems to come from the deepest instincts of the human psyche -- ones we feel we have outgrown or else forgotten, but in the moment of ultimate terror, can summon up as a survival reflex encoded in our nervous system from days of flint-tipped spear and lightning-gifted fire. The story may most readily be acquired today from the collection, Selected Stories by Fritz Leiber, published by Night Shade Books, copyright 2010.

Monday, January 10, 2011

In Defense of "Older" and "Genre" Fiction

Of course, the primary purpose of this blog is to highlight the power and enjoyability of short fiction, establishing how its literary effectiveness is on a par with the novel, which in today's creative output is fast eclipsing its sister form. This blog has also emphasized speculative and imaginative fiction over mainstream fiction, not because it does not recognize the validity of the latter, but to remedy a false perception. In America, that which gets defined as "genre" rather than "literary" is actually often as intellectually and morally stimulating as that which the establishment defines as "true literary art". This blog seeks to inspire an interest for good "genre" fiction among those who have been taught to ignore it or to have an uninformed prejudice against it. The problem with the definition of "genre" is that it implies limited scope, superficiality and childish artificiality. Yet there is bestselling, critically-vaunted mainstream fiction that exudes these very contemptible qualities beneath a veneer of gritty sophistication, and there is fiction pinned with the shining medal of "literary" which fails to come close to the profundity of insight found in much fiction branded with the admonitory scarlet phrase "genre".

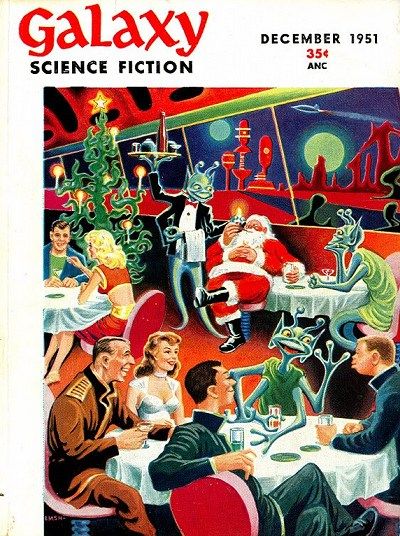

Now it will also be noticed that much of the short fiction presented here dates from over half a century ago. Part of this emphasis is again an attempt to rectify another imbalance, because the media always tends to favor the more recent. Short fiction flourished at that time, and that was where many authors were making their most important artistic statements, even if later, when novels became more important, they might rework those original succinct literary statements into long fiction forms. Much short fiction written after novels became the preferred reading format merely served as a way for an author to make a stylistic splash for notoriety's sake, while he or she otherwise saved his or her best storytelling ideas for the novel (where the real money now was). This is not to say there were not good short stories written in later eras; it is only to say that before that, when periodical fiction was preferred by the consumer, there was relatively more good fiction to be found in the shorter format. In those days you could read a short story from a magazine you bought at a drugstore, and find yourself looking out the window afterward, sighing with wonder, while you appreciated how the author had given you a new wrinkle in your philosophical outlook on life.

So having established these "underdog" justifications, I will now seek to address frequently voiced prejudices heard today on the internet against "older fiction", and show (again from an underdog perspective) why fiction from the peak era of twentieth century culture (or even of the nineteenth century) is still a worthwhile, enjoyable and even essential source of reading for the twenty-first century reader. The most frequent complaints I run across are: "naive", "idealistic", "simplistic", or even "quaint". What I have seen these criticisms applied to makes me wonder if the reader understands English. And then I consider what must be their normal diet of reading: what dominates contemporary fiction and graphic novels? Today, it doesn't matter if we're talking about literary, mainstream, comic books, or contemporary science fiction, mysteries, horror and fantasy, much of it has now fully embraced the flagrant culture of unashamed cynicism. Sexuality is all about maneuvers of power not love or tender affection. The quest is all about power not understanding. Violence is celebrated with artfully sadistic descriptions. Unsolvable dysfunctionality among the characters is proffered as an acceptable norm. Relationships are about relative advantage for selfish purposes. The heroes and the villains are indistinguishable, and their is no narrative voice decrying this. Women and men may be portrayed as equals in a technical sense, but women suffer awful violence and the men do not seem to have much more compassion than a "tough luck, babe" attitude, and no one troubles themselves overmuch in remedying the source of the problem except to enact revenge. In fact male characters suffer violence too and accept it like rain falling on their head. Violence always trumps any niceties of enlightened understanding or opportunity for higher purpose. The protagonists fight for what they want within the bounds of evil rules which are accepted as though they are laws of nature. As far as story-lines go, there are often chaotic shifts in point of view, gratuitous scenes that serve no purpose, hacked up plot-lines, and some form of violence is always the solution to the problem. No effort is made to rise above the traumatized psyche, but only to laughingly (if bitterly) accept such fractured states of being as supporting the sort of advantageously-damaged mind necessary to negotiate a world where everyone is out for themselves and conscience and scruples are for the losers. This, my friends, is the fiction of a doomed culture.

So if you want an alternative to stewing in the sickness of the moment, and realize you have a healthy respect for hope, conscience, expanding understanding, moral enlightenment and developing a higher consciousness of the miracle that is our cosmos, keep reading this blog to discover writers and writings that support this attitude of being. We have not degenerated as human beings, only that which is proffered as cutting edge literature has. Let us read again those who wrote about tackling the riddles and the problems of our existence and sought liberating truth and growth of compassion. What distinguishes these authors is their desire not to accept bland justifications for or explanations of things as they are (or to blindly accept the version of reality the cultural media encourages us to accept), but to question the validity of any permutation in our existence which seems to raise questions of moral consciousness, especially if we are expected to take it for granted. You will find that the best of these authors accomplish this through psychological subtlety, mutually broadening perspectives between interacting characters, courageous and skillful imagination, and some even employ a knowing humor that challenges the sturdiness of any new perspective adapted in the story. These authors are not moralizers. They are searching for answers that are not easy to obtain and sometimes have unpleasant or humbling implications. They do not make claims for the truth but they seek to find its direction. They do not preach, but their stories entice the engaged mind of the reader to include itself on the philosophical quests on which they drive their characters.

Now it will also be noticed that much of the short fiction presented here dates from over half a century ago. Part of this emphasis is again an attempt to rectify another imbalance, because the media always tends to favor the more recent. Short fiction flourished at that time, and that was where many authors were making their most important artistic statements, even if later, when novels became more important, they might rework those original succinct literary statements into long fiction forms. Much short fiction written after novels became the preferred reading format merely served as a way for an author to make a stylistic splash for notoriety's sake, while he or she otherwise saved his or her best storytelling ideas for the novel (where the real money now was). This is not to say there were not good short stories written in later eras; it is only to say that before that, when periodical fiction was preferred by the consumer, there was relatively more good fiction to be found in the shorter format. In those days you could read a short story from a magazine you bought at a drugstore, and find yourself looking out the window afterward, sighing with wonder, while you appreciated how the author had given you a new wrinkle in your philosophical outlook on life.

So having established these "underdog" justifications, I will now seek to address frequently voiced prejudices heard today on the internet against "older fiction", and show (again from an underdog perspective) why fiction from the peak era of twentieth century culture (or even of the nineteenth century) is still a worthwhile, enjoyable and even essential source of reading for the twenty-first century reader. The most frequent complaints I run across are: "naive", "idealistic", "simplistic", or even "quaint". What I have seen these criticisms applied to makes me wonder if the reader understands English. And then I consider what must be their normal diet of reading: what dominates contemporary fiction and graphic novels? Today, it doesn't matter if we're talking about literary, mainstream, comic books, or contemporary science fiction, mysteries, horror and fantasy, much of it has now fully embraced the flagrant culture of unashamed cynicism. Sexuality is all about maneuvers of power not love or tender affection. The quest is all about power not understanding. Violence is celebrated with artfully sadistic descriptions. Unsolvable dysfunctionality among the characters is proffered as an acceptable norm. Relationships are about relative advantage for selfish purposes. The heroes and the villains are indistinguishable, and their is no narrative voice decrying this. Women and men may be portrayed as equals in a technical sense, but women suffer awful violence and the men do not seem to have much more compassion than a "tough luck, babe" attitude, and no one troubles themselves overmuch in remedying the source of the problem except to enact revenge. In fact male characters suffer violence too and accept it like rain falling on their head. Violence always trumps any niceties of enlightened understanding or opportunity for higher purpose. The protagonists fight for what they want within the bounds of evil rules which are accepted as though they are laws of nature. As far as story-lines go, there are often chaotic shifts in point of view, gratuitous scenes that serve no purpose, hacked up plot-lines, and some form of violence is always the solution to the problem. No effort is made to rise above the traumatized psyche, but only to laughingly (if bitterly) accept such fractured states of being as supporting the sort of advantageously-damaged mind necessary to negotiate a world where everyone is out for themselves and conscience and scruples are for the losers. This, my friends, is the fiction of a doomed culture.

So if you want an alternative to stewing in the sickness of the moment, and realize you have a healthy respect for hope, conscience, expanding understanding, moral enlightenment and developing a higher consciousness of the miracle that is our cosmos, keep reading this blog to discover writers and writings that support this attitude of being. We have not degenerated as human beings, only that which is proffered as cutting edge literature has. Let us read again those who wrote about tackling the riddles and the problems of our existence and sought liberating truth and growth of compassion. What distinguishes these authors is their desire not to accept bland justifications for or explanations of things as they are (or to blindly accept the version of reality the cultural media encourages us to accept), but to question the validity of any permutation in our existence which seems to raise questions of moral consciousness, especially if we are expected to take it for granted. You will find that the best of these authors accomplish this through psychological subtlety, mutually broadening perspectives between interacting characters, courageous and skillful imagination, and some even employ a knowing humor that challenges the sturdiness of any new perspective adapted in the story. These authors are not moralizers. They are searching for answers that are not easy to obtain and sometimes have unpleasant or humbling implications. They do not make claims for the truth but they seek to find its direction. They do not preach, but their stories entice the engaged mind of the reader to include itself on the philosophical quests on which they drive their characters.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)