Comprising twenty-two pages, this novelette originally appeared in the August 1955 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. This tale explores several philosophical concerns whose specific permutations could only have arisen in our present technological age. Our relationship to machines, from Ancient times to the present, has always been to ease various burdens or onerous tasks of life, and soon thereafter to create greater uniformity and quality of products. More recently machines have been designed to solve problems of organization and order to maintain societal integration as human population densities have surpassed all previous norms. Machines have also been developed to make warfare more devastating and precise in its targets. Henry Kuttner projects all these uses of technology toward a logical future singularity of evolutionary unification whereby humanity surrenders its self-responsibility to computers and the robotic servants of higher artificial intelligence.

This may sound familiar, but in Kuttner's hands it has a different outcome than the typical science-fictional trope. In exchange for peace and stability, which the objective dispassionate synthetic mind of centralized planet-spanning computers can provide without error, humanity gives up self-governance. The computerized and wholly mechanized world supplies psychological satisfaction through virtual reality experiences transmitted by artificially induced trance states. All necessities are artificially manufactured and delivered as needed. Human society atomizes, as people become self-engrossed in personal whims and selfish pleasures. Machines exist only for humankind's physical health and egoistic pleasure. The moral compass of society loses its orientation as the need for struggle, competition, social discourse, human cooperation and emotional connection dissolve before computerized illusions of hedonistic and imaginative fulfillment. For this story, all this is already history. The author introduces us to a society that has just barely managed a slim generation ago to pull itself out of social implosion, by reasserting an active role in the material world. Human beings were failing to reproduce, because the underpinning social structures for basic human bonding had nearly entirely disintegrated. Faced with self-extinction, individuals came together to redirect the comprehensively mechanized-computerized world with a new fundamental program: enable human beings to become socially responsible again.

What these pioneers at rebuilding the mental construct of society face, however, is daunting: "conscience" itself has to be not merely re-learned but re-invented. The super-ego has to be reactivated. So in addition to dismantling technologies that provided for every comfort, pleasure and imaginative whim (so that human beings would be motivated to form social connections again with their fellows), negative reinforcement has to be introduced into a newly activated society that has been for so long in a technological womb of passivity. Here, Kuttner cleverly reinvents the mythological concept of the Fury in terms of a technological (and robotic) force of social control.

At this stage in the redevelopment of human society, people, while intellectually advanced, are still so morally infantile that murder is the essential form of moral corruption as people become re-accustomed to interacting with one another in complex ways. The title of the story is taken from a cryptic verse by Milton, who envisions that figure from Greek myth, the Fury, as a "two-handed engine at the door": the pursuing conscience of the person who mistakenly thinks he or she can escape the psychological implications of taking the life of another. In Kuttner's story, the Furies are robots that track down and follow those who have committed murder. The world is under pervasive sensory surveillance by a vast computer-mind maintained by a hierarchical human bureaucracy. An act of murder is inevitably discovered, and the perpetrator identified by the source of law and order: the wholly objective engine of artificial intelligence. The murderer then receives his or her Fury, a faceless, voiceless robot that follows them wherever they go, and keeps a vigil over them wherever they stay or rest.

These special robots will prevent their inmates from harming again, and at a carefully calculated moment, dependent on unknown factors of the individual, the Fury will execute the felon by any manner of assorted methods. The robotic Fury does not (and needs not) hinder the movement of its ward. This Fury of mechanical body can make of the entire world a prison for its charge, for the murderer can neither destroy it nor elude it. Its tenacious but serene accompaniment of its assigned felon is an example to all who observe the bizarre pair of the cost of taking the life of another: an act of harm, as the author points out, that cannot be practically undone.

In the story at hand, the supporting character, Hartz, a high-ranking administrator, induces a maladjusted citizen, Danner, into committing an act of murder, by demonstrating that he has the mathematical programming ability to undermine the normally unerring directives of the master-computer to impose the tenacious Furies upon guilty members of society. Hartz is a complex figure, despite not being the central character, for he believes in the moral rehabilitation of humankind so that it might not regress and lose its will to achieve character and reproduce itself. However, he is frustrated in being the penultimate controller. Hartz wants to be the master controller in this new alliance with the more perfect computerized/mechanized coordinators of human civilization. He still retains the regressed impatience of the id needing immediate gratification, and so, for all his sophistication of responsibility, he has not the restraint of desire found in a fully evolved human consciousness. The man above him, in short, is a mere hindrance, rather than a respected superior partner (in short, a recognized fellow human being) in the new project to rehabilitate humankind.

In the central character of Danner, Hartz sees a man even less evolved than himself, who can be persuaded to commit the very act that the institution to which Hartz belongs seeks most primarily to correct. As for Danner, he belongs to the last generation to enjoy the previous era of no psychological or physical challenges, and he lived long enough in that former reality to have it deeply imprinted on him. Thus Danner is incapable of fully embracing or finding higher satisfaction in the new reality, which requires effort and puts character-building limits on the boons of existence. Danner is deceived into believing that Hartz will use his hacking ability to derange the moral directives of the master computer, but Hartz knows that if he acts upon his knowledge, he will create a fault that may unravel the whole system of social control and thus humankind's general rehabilitation.

Despite his selfish ambitions, Hartz ironically has evolved enough to recognize that if he allows his faulty super-ego to have its way too far, it will ultimately defeat the purpose of the whole philosophical revolution to put a socially-responsible humanity back on its feet. So Danner ends up with a Fury as his constant silent companion, until the unknowable date when the robot will receive the algorithmic command from the central computer to destroy Danner. Yet Danner never succeeds in acquiring an inward sense of moral guilt, only an outraged resentment that his master-conspirator has somehow failed to protect him from the very fate that he had been guaranteed not to suffer. In return, he has gotten the promised unlimited source of wealth with which to pursue the pleasures Danner once knew in his youth before such things became rationed and contingent upon personal effort and social success. But where is the satisfaction when one is condemned to a mobile (though invisible) spot on Death Row?

Danner ultimately descends into murderous madness, as his unshakable Fury makes him an outcast even when his fellow human beings are willing to share his company, for his ubiquitous warden makes him attractive only to those who connect with him because of their superficial fascination with his impending doom. In the end, Danner seeks to slay Hartz, who can no longer put him off with promises to discover the reason for his failure to scramble the code of computerized justice and allow his minion to escape his punishment. At least he will have the double satisfaction of revenge and being put out of his misery afterwards by his mechanized jailor. Despite his efforts to temporarily separate himself from his constant attendant, the tenacious Fury still manages to prevent Danner from being able to kill again: that is, to murder Hartz. But Hartz does succeed in simultaneously killing Danner, just at moment the Fury foils his vindictive charge.

It is then that Hartz seeks to escape the same fate that befell the man of whom he made a dupe in his ruthless career designs. The very hacking code that he promised to use to deliver Danner from his sentence does indeed now save Hartz from sharing the doom of his morally clueless sap, the late Danner. However, the seemingly ruthless Hartz has by this point finally evolved just enough inwardly to have developed the fundamentals of a natural human conscience. At the end of the story, we come full circle, for we have the re-emergence in the mind of Hartz of the very psychological triggers that underlie the metaphorical construct of the Fury in Ancient Greek mythology. Thus the animated-metal symbol and imposer of afflicted guilt has been found disposable sooner than predicted. The flip side of Hartz (which is a nascent conscience) need not worry now over his cybernetic corruption of automated justice and its technological ramifications. If he is the first, he will not be the last to be pursued by the wholly mental-emotional construct of guilt -- now newly reinvented in him. He hears the footfalls of his Fury (a leitmotif in throughout the story), but there is no exterior robot to sound them. They fall within the silence of his mind alone. While this story may have been written fifty-seven years ago when the world still fundamentally operated by means of a clerk manipulating a filing cabinet, it feels intensely relevant and prophetic for the times in which we now live.

This tale may now be most readily obtained in this recent collection: The Last Mimzy: Stories, by Henry Kuttner, Del Rey Books, Copyright 2007.

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Friday, March 16, 2012

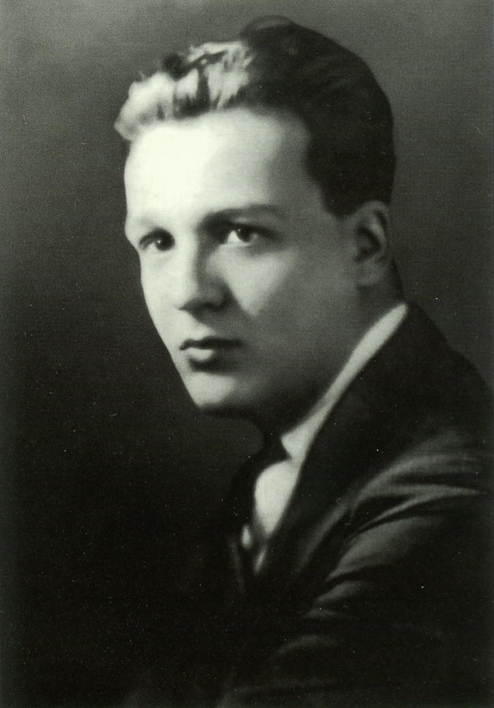

Review: "The Woods-Devil" by Paul Annixter

Originally published as a short story in February 1948 issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine, when it was still a sophisticated periodical like Harper's rather than a young woman's interest magazine like Glamour, this is a tale that has haunted me ever since I read it as a freshman in high school back in 1983 in a literary scholastic anthology. It was written under the pseudonym, "Paul Annixter", actually by Howard Allison Sturtzel, and later published ten years later in an anthology collection of short stories entitled, Devil of the Woods: A Collection of Thirteen Animal Stories, as by Paul Annixter, printed by Ayer Publishing Company in 1958. While accessible and of interest to the adolescent mind concerned with the emerging consciousness of newly adult concepts of self-reliance, this story follows the naturalistic school of literature that grew out of the school of realism, fully crystallizing its own distinct form from the late 19th century through the early 20th century. Naturalistic writing is popularly exemplified by Jack London, Joseph Conrad and Stephen Crane. This school of literature sought to make use of the new discoveries of natural science to extrapolate through fiction the animal nature of humankind buried beneath what was perceived to be a veneer of civilized sophistication, moral culture and artificially-conditioned social courtesy. Naturalist fiction writers sought to create imaginative scenarios where our artificial training to be civilized and philosophically composed met the naked test of the ultimate needs of survival or severe conditions of environmentally-induced psychological stress. In "The Woods-Devil" , the adolescent character, Nathan, living in the North Woods of Maine, must alone face the rigors and dangers of the wilderness in winter to sustain the now strained livelihood of his family's lonely homestead, because his widower father is laid up by physical injury. In the depths of an isolated world where survival hangs by a thread, he must face the "woods-devil", a creature his father has warned him of, and which is in fact a wolverine. What is so powerful about this tale is that the author has a narratively unobtrusive scientific understanding of the environment and the dangerous animal to which the young man is pitted, but he combines this with the perceptions of a non-scientific point of view, and the immediacy of experience and oral tradition of understanding to which simple homesteaders (and a boy a no less) are inescapably subject. Here we experience the tension of frightening folklore that is nonetheless based upon the practical edge of survival to which lonely inhabitants were subject in the Maine woods before the arrival of electricity and the broadened perspective and amenities brought by modern transportation. The central character Nathan, finds himself forced to assume an adult role because his father, the only provider remaining in his life, incapacitated by what the boy discovers is the psychologically discomforting revelation of physical vulnerability in his otherwise stoutly capable parent. He must now of necessity fetch the animals caught in the traps set by his father, so that they might have the income to see them through the winter. But there is a competitor for the victims of those traps: the woods-devil. While we may later learn that it is a once common creature of the North American ecosystem related to the badger, commonly called the wolverine, which the American Indians called the "skunk bear" for its stench of musk, ferocity of nature and dangerous proclivities, the author in this story drives us to understand this beast in terms of how a person on the ground with no scientific perspective was forced to cope with such an animal. There is the comfort of knowledge and the remove from untamed nature in which most of us have existed for over eighty years. The author vividly forces us to inhabit only the reality the young adolescent Nathan must face in the sylvan desert of this story. It would not even matter if he had had access to our scientific works of reference. Any such blandly empirical knowledge would not mitigate the danger he faces in his lonely journey to check the series of traps set by his father in the hunger of winter's wasteland. The boy has no contraptions to protect himself from this animal in the starving madness of winter's depths. The wolverine is an intelligent animal that cunningly and aggressively seizes the opportunities provided by humankind's snares of its natural quarry. Nathan is forced to compete with a creature, which for all intents and purposes, has a numinous effect on his psyche and exercises a very material threat to his physical wholeness and continuance. The young man must discipline not only his childish fears, but also the very real practical threat that even a full-grown man must face in his trek through the snow-bound wilderness of America's northernmost state. When I read this of an age level with the main character, I palpably felt his fear, his psychological tension, his willful determination, his inaugural sense of real vulnerability being risked for the sake of the survival of his household. One cannot exaggerate the skill with which Annixter puts the reader in the cockpit of this story's naturalistic sense of Nathan trying to balance his fight-or-flight instincts with a singular determination of mind to survive (and simultaneously help save the remnant of his family), and this without recourse to any form of help from a broader human community. When I read this as a newly-emergent teenager, I needed to cross no literary hurdle to identify with and be absorbed by the words of this tale. It was a story that I consumed as naturally as air and water, and it has left me pondering the nature of the human pioneer in the face of nature's less kindly side. Nathan's tenuous hold on survival by hiding in a hollow log when he at last crosses paths with the forewarned creature of hellish nature is an image burned in my mind as deeply as any actual experience I underwent in the real life I have since lived. Wolverines may be a merely a curiously irascible creature that we may watch and bemusedly learn about within the safety of our living rooms as the subject of a documentary on some educational cable channel, but Annixter reconstructed the intimidating and superstitious aura this animal must have once exercised upon the human psyche, when isolated settlers had no other resource than their bare wits and the practical wisdom of intimate experience.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)