Monday, March 29, 2010

Review: "City of the Singing Flame" by Clark Ashton Smith

Running a mere sixteen pages, this story, first published in 1931, devotes itself to a conceptual plot that artfully shirks definitive interpretation, yet hints at many possible explanations that only raise more questions of a nature that teases the capacity of the human imagination. The story's elements are so highly nuanced with implicit aesthetic, psychological and metaphysical depths, that the reader feels he or she has experienced something profound in the way of what may lay hidden beneath our deepest yearnings, and whither the anomalous features only half-noticed in our everyday reality may lead if properly recognized. To call this a mere trans-dimensional science fiction piece would leave out the author's special take on the whole question, which involves a creative-nihilistic nexus between different realms of shared space but variously pitched in quantum terms of how they share that space, though these spheres are imperceptible to each other. As for the nexus itself, it exudes the fine paradox of attracting the imaginative, the creative and the sensitive souls among sapient species, while at the same time destroying the ability of these to live their former lives with any satisfaction once they have tasted the music and beheld the mysterious source of the music at the center of this nexus. The other fascinating paradox lies with the native inhabitants of the nexus themselves, who may or may not have built the trans-dimensional gateways that lead to the temple complex that draws intelligent and inquisitive beings from a host of parallel worlds, but who definitely are immune to the allure of the music and that which creates it, even though they live daily in its very midst. What is more, the aliens (including human beings like us) who find their way to their dimension, raise nary an eyebrow of curiosity among these keepers of this strangely indiscriminatory nexus of supernormal attraction. For the natives, these exotic visitors are apparently as unremarkable (and apparently uninteresting to them) as the very air, and there is seemingly nothing to bed shared between them. The visitors are not there to socialize or do business with the natives, and the natives express no desire to exact any tolls on their enraptured visitors. The pilgrims who come to this city go there only for the Flame. The author of this science fantasy won renown in his time as a poet, prose poet, and writer of weird fiction, and it is in this tale that we find him negotiating a territory that combines poetic techniques of language, the imaginative intensity of a prose poem, the plot devices of a weird adventure, and the evocative style of palpable wonder from idealized scientific discovery. The story is tragic in a Neo-Romantic sense, but the mind of the reader must also marvel at its beauty as much as grieve over its ramifications. We are beings of mortal flesh with mortal imperatives, but we are also beings of spirit, with an instinctive need for spiritual release that creative forms of expression, however inspired, can never fully satisfy. And yet there is a sense in each of us, hinted at by those brief flashes of ecstasy in life, that there must exist some ultimate ecstatic release. In scientific terms, it would be a source of immaterial energy with which our very life force must share a primary origin, and to which we feel compelled to return, the closer we come to discovering it. And what if we stumbled on a gateway to this very source of our inner being? Could we resist returning into it by the sheer will to preserve our temporary mortal life and individual identity? Such is the challenge faced by the protagonist Giles Angarth, sometime writer of fantastic fiction, an obvious fictive analogue of the boundary-pushing author of this story himself. It may be most currently and affordably found in this collection: The Return Of The Sorcerer. Written by Clark Ashton Smith. Published by Wildside Press. Copyright 2008.

Review: "Of Missing Persons" by Jack Finney

There are some writers that are so good in their narrative style that they inadvertently trick your mind into thinking you can actually hear his or her voice telling the story to you. Once such writer is Jack Finney, and one of his more poignant stories of science fantasy is "Of Missing Persons", originally published in 1957, and numbering twenty-three pages. Part of the magic of this story lies in its protagonist being so sympathetically ordinary, so identifiably frustrated with the constraints upon aspiration into which a highly populated, highly competitive world thrusts most people. Charley Ewell, a simple but reliable bank-teller, may be outwardly average and mediocre socioeconomically, but inside he knows what life ought to be (if there were any justice in the world), and he senses within himself a potential that the design of the present world will never allow him to realize. He lives in one of the most bustling cities in the world, 1950s New York City, having sought out that metropolis to achieve a life more than average, but instead gets stuck in a rut with seemingly no exit. His prospects, social and professional are limited and tenuous. And then one day over beer in a bar, he strikes up a conversation with man of similar circumstance though of more experience. The sympathetic fellow-drinker gives him the most unusual advice: seek out this particular travel agency in an obscure part of Manhattan, and he will find a travel agent of a certain description who has a special folder about a place that could solve all of Charley's problems. However, Charley must be careful about it. He must say the right things that will motivate the agent to show it to him and reveal its implications. In a sober state on a succeeding day, Charley works up the nerve to do it, having been warned that if he doesn't come across in the right way, he will never see the folder. And if he doesn't properly appreciate what the folder offers, he will never get a chance at taking a trip there again. I will not spoil the surprising and fascinating story that unfolds, but suffice to say that Finney has a wonderful way of explaining quantum physics through ingeniously prosaic models, that he hides pearls within plain, dirty shells, and that he has an ingenious explanation for why certain people of great renown sometimes inexplicably disappear. This story can be most readily found in this recent collection: About Time: 12 Short Stories. Written by Jack Finney. Published by Touchstone. Copyright 1998.

Saturday, March 27, 2010

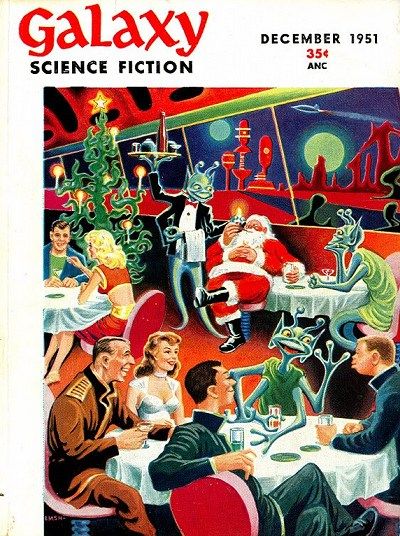

Review: "The Marching Morons" by Cyril M. Kornbluth

Where is our true 20th century or 21st century heir to the Mark Twain who wrote such tales as "The Man Who Corrupted Hadleyburg" and the short-story cycle, Letters from the Earth? In short where is the imaginatively talented American author who deeply perceives the flaws of our bumptious American culture, can satirize them with both devastating and hilarious effect, and yet still preserve the voice of humanity and compassion? This is no easy balancing act to accomplish, and Mark Twain might have been singular, even though American culture kept evolving the same foibles after he died, if only in new forms. I believe I have found the heir, though he too is now dead (even while his prescient ideas make him Twain's standard-bearer into the 21st century). The award for carrying on this tradition of rare satirical quality goes to Cyril Kornbluth, whose origins could not be more different than our Gilded Age Missourian, Samuel Clemens (aka, "Mark Twain"). Kornbluth was every bit the red-blooded American that Twain was, but he hailed from New York and wrote his greatest works during the banal hubris of Post WWII America. Despite their regional and temporal differences, I think these two chaps would have had a strong affinity for each other had they met, and even now are likely having some delightful conversations in heaven. To illustrate why I believe Kornbluth is Twain's heir (at least in terms of Twain's humorously yet still humane bitter side), I could cite quite a host of stories to back up this claim, including the most excellent, "The Little Black Bag", and, "The Cosmic Charge Account". I certainly will eventually write proper reviews of those two short works one day. But the best illustration of what I am talking about in particular right here is "The Marching Morons", a twenty-four-page short story, originally published in 1951. It is insidiously shocking, endlessly surprising, insanely hilarious, and yet at the same time deeply sobering, and presents a very probable future if sociological trends (which began in the nineteen-fifties throughout the Western world -- not just America, and continue to this day in the twenty-teens) do not change. What Kornbluth is talking about is the tendency of financially prudent and career-burdened folk (reflective of their higher intelligence) to decide (at best) to merely replace themselves reproductively (i.e., have two children), but more often choose to only have one child -- or even no children at all. Well, Kornbluth looks at this sociological phenomenon observable in his own day (say what you will about the plethora of baby-boomers), and asks, what if this trend doesn't change as the decades and centuries wear on? How will civilization survive if it is only those of average or low intelligence who have oodles of children? His projection in the story at hand is a society daily on the brink of collapse if not for the exhaustive multi-vocational talents of a few million extremely dedicated people of true intelligence managing the lives of many billions of people whose average intelligence over the centuries has degenerated to "45" on the I.Q. scale. This minority works behind the scenes, but is fast approaching a limit in their labor capacity to offset a total disaster stemming from what is euphemistically referred to as "the Problem". In short, this altruistic minority of intelligent and properly reasoning folk are the slaves to the population mass, of whom the latter believe they actually run the world. There are a host of normal human foibles that Kornbluth explores in their gross expansion in this dystopian future, including machisimo-driven warfare, illusory technological power, mindless carnal appetites, adolescent escapism, not to mention vehicular debacles in aerial and street traffic due to absurdly distracted pilots and drivers. For those who have won their way to positions of "official" responsibility among the more intelligent morons, the truly intelligent minority (working in their humble, low-profile positions) use post hypnotic suggestion strategies to prevent these "leaders" from sending their societies or organizations into crisis situations. Throughout the story Kornbluth employs multiple layers of psychological absurdity that create avalanches of humor in the reader's imagination, and such mental impacts will elicit rude outbursts of guffaws if you happen to be in a public space. However, the story never loses its sober interest, which is the struggle of this covert organization of the remaining intelligent folk to avert the tipping point of global disaster. The protagonist of the story, a true anti-hero, is John Barlow, a corrupt real-estate business man, with a horse-trader's gift of persuasion, ruthless self-interest, and the wheeler-dealer savvy of a true urbane cynic. But he does not belong to the age in which this story takes place. He has been preserved by an electro-chemical mistake performed at a dentist office in the late twentieth century, and the crypt that has held his uncorrupted body and catatonic consciousness is fortunately (though accidentally) discovered by one of the intelligent renaissance men, who revives Barlow using a simple hypodermic procedure. After a comically fantastic odyssey in which Barlow realizes he has reached a future where the world has been turned upside down, the secret organization of the remaining intelligent people of Earth, realize that not only is Barlow someone who belongs with them, but that he also might possess a character of insight that could save human civilization. Of course, as soon as Barlow realizes how much they need him, Kornbluth takes the opportunity to show in his protagonist all the stubborn short-sightedness, bottomless egotism and inane provincial bigotry that most of the financially successful white men of his own era exude, made all the more ridiculous when compared with the self-sacrificing and humanely rational industriousness of the intelligent minority trying to preserve the human race in this future setting. In the end, Barlow really does save the human race, but his solution and methods are bitter in their resort, absolutely dictatorial, psychologically adept, tin-pan alley hustling updated to the umpteenth power, and unconscionably deceitful. As for Barlow's fate after the terrible work is done, I will leave that for the reader to discover, but the story's resolution brings a sobering relief, and a contemplation not lending itself to a restful state of mind. This tale may be found most recently published in: His Share of Glory: The Complete Short Science Fiction of C.M. Kornbluth. Edited by Timothy Szczesuil. Published by NESFA Press. Copyright 1997.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Review: "The Gentle Boy" by Nathaniel Hawthorne

What is great about Hawthorne is that, even when he is writing straight fiction, his stories are infused with a sense of the mystical playing with well-drawn realism. And then when he is writing historical fiction, the reader feels that he has actually come out of that time, for he not only understands the material, political, religious and psychological culture that he treats, but also the diction. I have read primary sources from the Puritan period, and Hawthorne is spot on! Then combine this with his own beautiful moral sensibility and keen understanding of the rugged paths of the progress of humane behavior, and we have a truly powerful writer on our hands. What one must also remark upon is that Hawthorne, unlike some authors of the Romantic Period, does not fall into extraneous digressions. His every word and ornament of description economically serve the central purpose of whatever tale is at hand. His short story, "The Gentle Boy" illustrates well all these qualities. This tale was first published in 1839, and numbers 29 pages. Though it takes place in the mid seventeenth century, it happens to speak directly to a globally pervasive problem in our own time: religious bigotry. The story deals with the tragic and inhuman prejudice of the Puritan sect toward the Quaker sect. Yet it is even-handed in terms of the flaws of these two contending parties. Hawthorne's tale also explores the self-destructive and family-destructive foolhardiness bound up in the then Quaker ethic for a kind of evangelical activism which provokes political violence and incarceratory privation toward themselves, often leading to martyrdom. The "gentle boy" of the title is one "Ilbrahim", a foundling taken in by a kindly Puritan couple who has lost all their own children to disease. The child has lost his father, who was hanged on the gibbet for the recalcitrant heresy of Quakerism, and whose mother was banished to the western wilderness unclaimed by European habitation for the same theological crime. In the course of the story, the kindly couple who nurture and heal the child enjoy not praise for their compassion but increasing ostracism, until they are utterly friendless and must even endure economic ostracism from the business of the community. Their adopted child too suffers a terrible beating from the fellow children of the community, who have been taught by their parents to despise Ilbrahim as a child of deviltry, despite the fact that this Quaker foundling has the kindest and brightest of spirits. As time progresses, both the spirit of the child and of his enduring adoptive parents begin to break down; to their credit, they never blame the child for their misfortunes, but continue to love him the more and adhere to their religious faith. The father, however, so alienated by his fellow Puritans, decides to befriend Quakers entering the community and suffers many fines for it when he is caught sheltering them or in their company. He even covertly converts, but it is not because he believes in their tenets but because he believes there is something more deeply flawed in his own sect. The end brings a surprise that results in a profound psychological healing for the child Ilbrahim, and a credible and progressive reversal (though costly in human terms) of the Puritan community's attitude toward people of the Quaker sect. I have left much out for the reader of this tale to discover, including the fascinating and recurrent character of Ilbrahim's banished mother. A good affordable and currently available edition in which to find this story is: Twice-Told Tales. Written by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Published by Modern Library Classics. Copyright 2001.

Monday, March 15, 2010

Review: "A Saucer of Loneliness" by Theodore Sturgeon

First published in 1953, his thirteen-page short story packs a wallop every bit as powerful as other literary critiques of the degeneration of the spirit of democracy and personal freedom in America during the era of McCarthyism, such as the The Crucible by Arthur Miller, or Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, though it does it miniature. For all that, the concentration of it moves the emotions of the reader quite unexpectedly, and creates a whole new vision of the two principle characters at the end than one had of them at the beginning. Sturgeon's storytelling here has the fecund organic development that makes people forget where they are or that they have any other concerns than the characters and imagined world they are reading about right now, however fictive. The story begins in media res, but I will set the reader up by describing the past that has led up to the matter of crisis that sets the story in motion. The central protagonist is a psychologically-harrowed woman, who a few years ago, as a simple young woman, suffered a special grace, much like Joan of Arc did when that peasant girl began hearing the voices of angels at the old sacred tree near her village. But we are now in the Atomic Age, and our female heroine has gone out to Central Park in New York City to enjoy the very first touch of spring. She has walked into its inviting depths like many that day, and felt the elemental power of nature sweep away the hardness of city life, and as we later learn, the personal hardness of her family life. The grace she receives is the visitation of a small flying saucer, which out of the many visitors milling about the park, chooses her over whom to hover and shine. From it emerges a fascinating humming sound, which strikes fear and stubborn curiosity in the other people there, who form a thick circle some distance from her and the saucer. One man gives spontaneous utterance to his thought that the saucer appears like a halo over her head, and hearing this, the girl loses some of her fear; the notion occurs to her that perhaps this object does not mean her harm but rather, it may value her in some way. Soon the humming sound takes on a melodious climax, and then the saucer suddenly falls silent, loses its metallic glow, and falls to the ground, devoid of all animation. The young woman faints from the release of this intense experience coming to so abrupt an end. She wakens to find a policeman, a reporter and a crowd of fearful rumormongers barely held back by other policemen racing over to contain the situation. Her first instinct is to tell the policeman who protects her that the saucer spoke to her, and that she would like to share its message with him, but the policeman is too distracted by the mounting chaos of the crowd and the unreadable instigator of this commotion, now lying dull and arcanely listless on the newly sprouting grass. But then a bland well-dressed man enters the scene and takes over. He is with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and he renders obsequious the formerly swaggering beat-cops, commandeering them to ward off the crowd while she is borne away on a stretcher to an awaiting ambulance. In the meantime, she is warned to say nothing of what the saucer communicated to her mind. Once at the hospital, the young girl is given her own private bedroom (something she has never enjoyed in the urban poverty of her life), and she is shown a care and personal consideration she has never before known. But however spiritually hungry she is to be valued as an individuala, she soon sees through to their ulterior motives. They question her exhaustively about every minute detail of her simple and brief existence. The questioning becomes interrogation, and it is all to get her to slip up and reveal what the the saucer said to her. For you see, she has decided in the interim that she will not tell anyone about the saucer's message. After the medical authorities have pronounced she has suffered no physical harm from the saucer and retains no psychological trauma, she is sent to court, and her own assigned defense attorney is not in sympathy with her right and will to remain silent, to her privacy. She is jailed for contempt of court, and the interrogations continue, but no legal charge will hold her much longer, and she is finally released. Yet the world of freedom she returns to has utterly changed from what she last knew now months ago. Her alcoholic mother will have nothing to do with her, feeling her daughter has brought her ill fame in the public eye for possibly consorting with a foreign power. So she sets off alone, but the wild publicization of her in the newspapers, radio and television have made her notorious as a suspected mole whose secret knowledge might harm the security of the country. She must go from job to job, hoping not to be recognized too soon. Frequently she meets nice-seeming men who would court her, but they always end up showing their true cards by asking her about what the saucer told her. Always when she is on such dates, she and her date are followed. These men are not interested in her but the potential power she keeps locked up in her mind, and some of these pretend courters are agents of foreign powers as well as being agents of her own government, just as the men tailing them are sometimes fifth columnists and sometimes legitimate men of national security. To escape the madness has become her life, wherein her spiritually malnourished society's irrational fears , lust for power and craving for scandal have all been witheringly focused upon her, she moves to a sparsely populated coast, where she sets up a house-cleaning business, enabling her to work alone unmolested. She takes up reading as she never had before, but it is no substitute for a real life with loving people in it to share it with her. She find another temporary solution (though a more lasting one) to preserve her sanity and stave off her compounded loneliness, for even before she had encountered the little saucer, she had been lonely the way many unloved children are, even as they have almost reached full adulthood. She begins writing messages and sending them out in bottles, hoping that this pure and anonymous form of communication will reach someone real. She imagines how such messages from her might prove nurturing to souls as lonely as herself, and so she entertains a kind of vicarious companionship with unknown others like her across the world, who also live lonely by the vast ocean sea. But in the end, the loneliness is unbearable, and the companionable sea has now become a lure to her for real oblivion. And yet, her messages have reached someone, a person intelligent enough to study to ocean currents and prevailing winds, and thereby to discover their point of origin. Moreover, this person has sensed in her messages that she must be found before it is too late. I leave it to the reader to discover her fate and the nature of this person who seeks her, not to mention the very surprising thing the little saucer told her. I encountered this story in an original collection called E Pluribus Unicorn, published in 1953 by Ballantine books; it was printed in a 35-cent paperback I found in my grandfather's attic library collection after he died. It is out-of-print now, but it may more be more readily and affordably obtained (having been reprinted numerous times through the decades in this form) than its most recent publication, which was an expensive, quality-production small-press effort that is now also out-of-print: The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon, Volume VII. Published by North Atlantic Books. Copyright 2000.

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Review: "The Eyes of the Panther" by Ambrose Bierce

Originally published in 1891, this eight-page short story haunts the mind long after one reads it. It is written in a cadence meant to be read aloud, an oratorical sense of the placement and shape of perfectly chosen words and phrases. The power of this brief tale resides in its economic style, its elegantly understated diction, the facts left tantalizingly unsaid amidst the bare portentous facts stated, and the fact that it describes a situation that seems oddly familiar yet at the same time utterly unfamiliar. There are hints, there are matters and things bizarrely reminiscent of something human beings learned long ago when we were still hunter-gatherers daring by necessity the predator-haunted forests and meadows of the Paleolithic Age. But in the end, we have a story that embodies the most ancient meaning and most ancient nuance of the word "weird": the intervention of an uncanny destiny. The story takes place when the eastern half of the United States was still a wilderness to be explored and gradually pocked with small farms that represented personal liberty, however fragile the hold upon freedom of those pioneer homesteaders in their hardscrabble stake. The story focuses on two spare generations of one homesteading family, and a young professional man hoping to marry into it and bring it a happier third generation. And yet the woman that has won his heart, and who indeed treasures his own, is compelled to reveal to him, at the moment he proposes marriage, that she has come to the realization that she is insane. As to why she is, she attempts to explain through a story of long ago, when her own mother was about her age. In that time, there was no town, no developed agrarian landscape, as they now enjoy, but only the little one-room cabin that her father and mother built amidst the looming forest. They knew a rough contentment, with a simple farm, a thriving babe from their union to celebrate in their mutual nurturing, and no one to yet bedevil them with the onerous pinpricks of officious civilization. They had for a brief while their Eden. But the wilds were still dangerous, and in the purity of their existence, the mother had a kind of clairvoyance that her husband did not. He set out one day to go hunting, though his wife pled with him to delay his intention but another day, that it would mean the end of all their future happiness if he did not heed her. He dismissed her superstitiousness when she could only claim that her insight came from a dream, and so he left on his errand. He had been supposed to return at suppertime, but he did not, and when night fell, she put out a candle on the sill of a window whose shutters she parted, as a little beacon for his way back to their little home. She otherwise barred the door carefully against any threat the darkness might bring. But the candle burned down and flickered out, and still he did not come, and she in the meantime had fallen asleep comforting herself by comforting her baby girl. In the very pit of the night she later wakened and spotted a pair of glowing eyes appearing in the window she had left open and where once her candle had glowed. These were feline eyes, and at a level and of a size that could only come from one the dimensions of a panther, ostensibly standing on its hind legs and resting its paws on the sill. Paralyzed with fear, and knowing the big cat could leap in far quicker than she could slam the shutters closed, she got to the farthest corner of the cabin and shielded her babe with her body. What followed I will not reveal, nor does Bierce himself fully reveal it, though I will tell you that the young woman telling the story was not the wee child in the cabin that night, that the father did finally return the following morning, and that the storyteller's mother, the same woman in the cabin that night, died giving birth to her second child, the narrator of this incident. Getting back to the present, the suitor of the young woman decides his ladylove is indeed insane, but not for the reasons revealed in her story; rather, the weird story is a reflection of her madness. He agrees to her wishes that he break off his suit, and takes up the life of a bachelor while setting up his law practice in town. Though he resides in a boarding house, he spends time off in a cabin he built for himself near a woods in the surrounding countryside. It is while at this scenic retreat one night, that the very encounter experienced by his former lover's mother now happens to him. And yet he, unlike that luckless pioneer woman long ago, is armed. He fires upon the glowing-eyed panther peeking through the breeze-way of his open window. Neighbors come running at the sound of the gun-blasts, and a search is mounted for the creature, which has dragged itself away through a swath of flattened grass. The morning light reveals a bizarre tragedy, and the implications to the reader are multiple, perplexing, fascinating and jarringly revelatory. This story can be most readily found in the excellently organized single-volume compendium of all of the author's fiction (still in print): The Complete Short Stories of Ambrose Bierce. Compiled by Ernest Jerome Hopkins. Published by the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 1984.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

Review: "The Sorcerer of Rhiannon" by Leigh Brackett

This story was first published in 1942 and is twenty-seven pages in length. The "Rhiannon" of the title does not refer to the woman of Welsh myth but several rises of land in the Martian desert that were once the seat seat of power behind a mighty empire of seven kingdoms, some 40,000 years in the past, when Mars was still a blue planet like Earth and they were islands. The sorcerer of the title bears that description only because his ancient scientific knowledge so far outstrips that of the present that it may as well be sorcery that he practices by comparison to that known by the civilization that currently prevails. Yet the sorcerer is not the hero of this story (at least not at the beginning), nor can he even be called fully alive -- he is a self-preserved consciousness seeking a living sentient form to animate his will and resume an anciently interrupted purpose. Despite the millenia he has slept, he is a Rip Van Winkle with a vengeance, whose ambition and learning lead him only belatedly into the bewilderment that played havoc with Washington Irving's character. His name is (or was) Tobul, and he was a usurping admiral, descended of a half-civilized race of wilderness nomads, eager to overthrow the serene power of a much older civilization and race, which, ironically, had nurtured his race of Martian nomads out of their savagely desperate lives. But the real protagonist of our story is far less glorious. His name is Max Brandon, an Earthman and adventurer who has adapted himself to the harsh Martian environment and who knows his way around the dangerous dealings of the black markets of the illicit collectors and the lethally competitive treasure hunters (not to mention the zealous officers of the law seeking to protect the fragile heritage of Mars and consign the pillagers to the lunar mines of Phobos). But though Brandon is bent on making a living from plundering the lost archaeological remains of Mars' distant glory days, living at the behest of no man, he also retains a latent Romantic longing to somehow know those incredible days that are now dead, aside from the priceless artifacts left behind. At the beginning of the story, we find him in desperate straits, having gotten separated from his aircraft by a sandstorm and on the last of his supplies as he has wandered in search of an oasis he knows deep down cannot exist. He is a man of indomitable will however, and that capacity to push beyond mere physical endurance has made of his body a perdurable vessel of strength. His present fix stems from his survey of a potential topographical marker leading to the lost treasure of Rhiannon, and both his blind wandering and the vacuum force of the sandstorm converge upon the revelation of a long buried Martian galleon, bared of the swallowing sands that filled the ocean beds after they went dry, brought to dismal light for the first time in tens of thousands of years. Its deck is titled just sharply enough that Brandon can clamber aboard, and what he finds in the captain's cabin not only saves his life but leads him on a path to his original goal that is anything but what he originally intended or could have imagined. There are others who come into play, principally two women: one resurrected from the time native to the sorcerer Tobul, by the name of Kymra, of the Prira Cen, the oldest and greatest sentient race to evolve on Mars, and she, Kymra, is the last of her now legendary kind; the other is Sylvia Eustace, a young, fit Earthwoman from a wealthy colonial family who has a tomboyish command of flying machines and the weaponry of survival, a native's understanding of the Martian world, an independent will to match the pride of any man, and who loves Brandon, her "Brandy", enough to marry him and seek to save him from his own foolhardiness. Here are the rich elements of an interplanetary fantasy, brought together by a writer who can turn a phrase of dialogue that revels in the poetry of life-hardened wit, while at the same time evoking a world of poetic vividness and ambient Romantic yearning. In this adeptly wrought tale, Leigh Brackett displays through her storytelling craft her claim to be called the "sorceress" of Rhiannon. After years of languishing in the crumbling remnants of pulp magazines from long ago, this story and others just as wonderful can now be happily found and lastingly bound in this collection: Martian Quest: The Early Brackett. Written by Leigh Brackett. Published by Haffner Press. Copyright 2002.

Friday, March 12, 2010

Review: "The Pin" by Robert Bloch

First published in 1953, this twelve-page short story exemplifies the provocative power that can stir within the short story form when in the deft hands of an imaginative craftsman such as Robert Bloch. What so captivates the reader in this tale stems from the fact that it provides a modern psychological update on an ancient mythical archetype, and dramatically explores the negative ramifications (in a contemporary urban context) of an equally ancient wish-fulfillment tale, which at first glance seems to be a positive thing in terms of correcting an apparent fundamental unfairness in life. Bloch's plotting is subtle and perceptually teasing in an eccentrically mysterious fashion, using very prosaic elements to clothe occultic dramatic elements. The protagonist, Barton Stone, a simple artist seeking the perfect refuge amidst the hustle and bustle of the city, and finds a dingy but spacious loft apartment in a quiet run-down building with few tenants. Here is a rare place that might facilitate his focused creative energies, but unexpectedly it is in this overlooked place that he crosses paths with the unlikeliest of destinies. This is a story of misplaced curiosity that leads to a career change of truly terrible responsibilities. To his credit the protagonist tries to make the best of things once he finds himself trapped in his new role (which is truly cosmic in proportion), for his new work ties in with his natural will toward compassion for the world and its miseries. However good intentions do not always lead to just decisions, and he is gradually convinced to adopt a policy of cold sober justice, and of a magnitude that escapes the moral comprehension of most mortals. In the end, his individual personality is finally absorbed and subsumed by the inherited identity necessary to his new vocation. His inner being has been reduced to the truly ancient official mask that goes along with the onerous function into which he has inadvertently lured himself. The man who was the artist no longer exists. It has been replaced by a man whose "creative" material is at once the dullest and the most tragic, and whose artist's paintbrush has been traded in for a simple pin whose prick has the final word in the hierarchy of power. And this power is utterly humbling. The reader can most readily find this story in this relatively recent collection (still in print): The Complete Stories of Robert Bloch, Volume 1. Published by Citadel Twilight. Copyright 1990.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Review: "Faith of Our Fathers" by Philip K. Dick

First published in 1967, this twenty-five page short story has a fully realized setting, rich enough for the author to have turned it into a quite fascinating novel. Nevertheless, Philip K. Dick's choice to keep it a short story of special focus makes it quite powerful. That focus, amidst an interesting social political milieu, raises the following correlative questions: is the source of continual human failure to live up to its better nature (despite repeated near successes) ultimately derived from a disruptive force that is extraterrestrial, or perhaps even what might be construed by mere mammals such as we as being relativistically de facto "divine", and does such an entity subsume good and evil in a mystical way incomprehensible to the practical hopes of the earth-bound human psyche? On the exterior, the reader encounters the very thing most feared during the Cold War among democratic capitalist nations: most of the world has fallen like dominoes into the Communist fold. There are still isolated places of resistance (by implication geographically unimportant) and annexed places not yet fully acculturated to the Communist ethos, but it is only a matter of time before complete totality will be realized. There are references to a global war many years before, hard fought by democratist groups and nations, but decisive victory went to the Communists. For many decades since the global empire of the Communists has been wielded by a supreme ruler taht won them that war, and the Party has ironically (though unintentionally) assigned to him very feudal Chinese titles of a florid and lengthy nature, doubly ironic because he is in fact (for the record at least) a Caucasian originally from New Zealand. People sense their ruler should be far too old to control this far-flung poly-ethnic cosmopolitan state, but he always appears in his television broadcasts as physically maintaining an ideal middle age. The most remarkable technological innovations shaping existence, aside from robotized taxis, have been devoted to the maintenance of totalitarian control: television sets which act as video cameras to monitor the behavior of the citizens in their private homes and ensure their attentiveness to televised public addresses from their supreme ruler; videographic manipulation of appearance so that an authority figure appears in the race and with the ideal features that will most appeal to the dominant ethnicity of a particular broadcast region; "conapts", which are citizen apartments discretely designed for complete intelligence infiltration by the government; and unknown to all but the Party's inner circle, the lacing of the potable water system with a drugs that maintain an illusory perception of reality that maintains people's faith in the system of control. But enough time has passed, that the idealist period of struggle against ideological threats of any political strength has long passed, and now people are either beginning to become doubtful and distrustful of the need for such severe controls on their individual freedoms, or have degenerated into becoming ambitiously obsessed with petty punitive monitoring of their citizen neighbors. This fragmented psychological situation most tellingly reveals itself through the protagonist, Mr. Tung Chien, a mid-level Party official working for the Postwar Ministry of Cultural Artifacts, which functions as a bureau to help orchestrate educational initiatives in areas where there are remnants of alternative thinking, by using cultural media familiar to those populations not wholly acculturated to communist philosophy. Chien is now on the brink of promotion, but first he must pass a test of discernment which (unknown to him at first) contains a trick. He is made to believe that the analysis is merely to help the Party decide the nature of wrongheadedness infecting one of its elite schools of education in California, and thus prove his competence to handle a special project to recruit and train bright young Americans into their local Party machine. However, the true nature of the test has more personal ramifications for Mr. Chien. If he makes the right choice, he will have the opportunity to enter the inner circle of the Party. If he fails he will be demoted into an obscure office. This is secretly revealed to him by a woman, Tanya Lee, belonging to a subversive group of surprising resources, who visits his conapt. That she runs such a risk with an important member of the Party is mitigated by an initial revelation she tricked Mr. Chien into experiencing earlier. A war veteran on the street peddling small items, whom the law requires citizens to patronize, sold Chien a packet of supposedly medicinal powder. This war veteran is really a fellow agent of Lee's. The content of the packet has the appearance of snuff, which entices Chien to later snort it during a boring broadcast from the supreme leader. But the powder is actually a counter-hallucinogen called "selazine", now very rare because it exists only in remnant supplies left over from the laboratories of anti-communist groups. Through this counter-drug, Chien perceives for the first time the supreme leader as he really is: something not physically human. Though Chien has reached a point in his life where what he most desires is to attain a place of relative comfort and personal liberty within the Party, he decides not to have Lee arrested because he realizes that she is no ordinary subversive: she belongs to a group that simply wishes to understand what indeed is controlling their society and what its motives may be. Lee wishes to recruit Chien as an intelligence operative for their group, but Chien remains on the fence despite the disturbing revelation of the television broadcast. Eventually however, covertly re-supplied with more of the selazine, he decides to follow through (at least to satisfy is own burning curiosity) when he is invited to high-level Party banquet to personally meet the supreme ruler. What happens at this banquet I shall leave for the reader to discover, but it instigates an ending in which the most primal expression of humanity is affirmed in a world now known to Chien and Lee to be otherwise bound up in a game, both sides of which are played by the same person; and that person has no sympathy for what is truly human. Here we have a potent short story that makes definite metaphysical innovations on the dehumanizing qualities found in such seminal dystopian novels as Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and George Orwell's 1984, by transcending the question of what ideological force results in totalitarian control, and questions whether the impetus of such absolute control over people's lives can possibly stem from the evolutionary psychology of the human species. Indeed, the story's secret points to the most paranoid but most compelling answer for what seems a most irrational way to manage human life, and which remains to this day, a seemingly insidious temptation creeping into all governments and nations, despite the lessons of history and the better natures of their traditional leadership. The reader can most easily find this short story in: The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick, Volume 5. Published by Citadel Twilight. Copyright 1992.

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

Review: "Parasite Planet" by Stanley G. Weinbaum

This story of twenty-eight pages was first published in 1935. During that era of speculative and fantastic fiction, tales tended to consist of headlong cartoonish action, unabashed anthropocentrism, cardboard character stereotypes, melodramatic language, slangy dialogue, unrealistic motives, naive assumptions about astrophysics and extraplanetary geology and biology, all topped off with uber-male chauvinism and melting females. There were rare exceptions to this pulpy ethos among writers of popular fiction, like H. P. Lovecraft for instance, but Lovecraft was more on the darkly weird end of the imaginative continuum. Front and center on the science fiction wavelength of the spectrum of fantastic literature stepped Stanley Grauman Weinbaum, who ripped through all those fictional tropes that the editors thought were sure-bets for periodicals sales, and introduced stories that science fiction fans had been hoping for but had only enjoyed as hints of possibility in previous writers. In a streak of incredible short stories and novellas written over a period of roughly two years, Weinbaum had fans cheering him on in the epistolary columns of the magazines. Then he died suddenly of cancer. But he was a signal light to a new generation of writers and editors, who realized they could write and published science fiction that picked up where Verne and Wells had left off, but in light of modern developments of psychology, physics, chemistry, and biological knowledge. Weinbaum's "Parasite Planet" is a perfect example of all that is best in the proto-revolution he mounted (it would have been his revolution to fully initiate right there in the mid-1930s if it had not been temporarily aborted by his untimely death). While this story takes place on a theoretical Venus that our modern space probes have proven cannot be, Weinbaum imagined his Venus in terms of the best scientific inferences at the time, and he built logically and vividly from there. However this point really doesn't matter in terms of the intrinsic value of the story tiself, for so keenly and thoroughly has Weinbaum thought out this planetary environment, that something like it must feasibly exist somewhere in this universe. Weinbaum posits the possibility of a planet whose heat, humidity and fecundity synergistically produce such biospheric super-abundance that life teems, thrives and feeds upon itself in a manner that makes the lushest rainforests on our own Earth seem like a static desert by comparison. All this highly active adaptation and counter-adaptation, hyper-competition and hyper-tropism results in an extremely dangerous and almost untenable environment for anything so fragile as a human being. And yet Weinbaum introduces to the reader a plausible adventurer who has pitted himself with ruthless intelligence and tremendous physical agility against this world in order to collect a rare native plant species whose medicinal properties can bring actual physical rejuvenation. If he can actually get his harvest of them off the planet, it will make him independently wealthy and fund his dream-projects as an engineer. The name of this intrepid go-getter is Hamilton "Ham" Hammond, and he is a tough yet latently compassionate American, occasionally trespassing across the British treaty zone of this imperially carved-up planet. The story is ingenious on many levels, among them its visceral portrayal of the struggle to survive against a seemingly endless array of rapacious molds, animal-like plants and human-like animals that can do everything from accelerating the entropy of any artificial structure to consuming life and limb with indifferent savagery; and all of this is vividly rationalized by the author in terms of biochemistry and instinctual behavior patterns. But the story gets better. There are others who brave this incredibly hostile environment, and we get to meet one as interesting as Ham: Dr. Patricia "Pat" Burlinghame, a cool yet latently sentimental British biologist studying in the field, cataloging the dynamically clever flora and fauna of this planet. If in the character of Ham, we encounter a skillful opportunist who is merely seeking a means to an end, in the character of Pat we encounter a woman who can match Ham in survival skills and practical athleticism, but who treks this planet for reasons completely the opposite of mercenary. She is an idealist for pure scientific endeavor: knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Ham is a fortune-hunter whose real interest lie far away from the hellish world in which he must abide for the nonce. When these two willful personalities cross-paths in this bewildering chimerical environment and amidst thisself-consuming ecosystem, they immediately fall into psychological and political conflict, despite the dangerousness of such a distraction when the world about them is hungrily pitted against them both. Slowly the urgent demands of practicality and survival compel them to set aside their differences and join forces to escape from the writhing overabundance of the hot zone of Venus obtain to the planet's more desolate cool sun-denied mountainous zone, where there is a pass leading to a protected colonial community. But first they must get past unforeseen, cryptic and inventively hostile bands of native protean sentient beings too intelligent to be deceived but too irrational to communicate with. So here is a story of convincing intellectual and physical equality and cooperation between the genders, leading to a mutual respect and understanding between two people that is hard earned but well earned. The psychologically-realistic dialogue exhilarates like a well-played tennis match, and the approaches of the two protagonists to getting out of scrapes in the most surprising scenarios is exhilarating. And all the while the enrapt reader is learning through pertinent facile descriptions and active contextual revelations the scientific ramifications of all these characters experience. Few writers have realized so much in novels ten times the length of this short story. The reader can most easily find this story from its appearance in this most recent collection: Interplanetary Odysseys. Written by Stanley G. Weinbaum. Published by Leonaur Limited. Copyright 2006.

Monday, March 8, 2010

Review: "The Dead Past" by Isaac Asimov

This thirty-seven page short story was first published in 1956. It represents the provocative power of science fiction at its best, encompassing a dynamically balanced treatment of both a technical scientific theme and its depth of impact on a future human society. The plot of the story gradually but steadily weaves the two spheres of restless humankind and its half-blind creations into an accidental struggle with madness, as they interactively evolve in ways that cannot be predicted either by the original intentions of the scientific innovators or the reasonable presumptions of human psychology. New pathways lead to new ways to express or engender human pathologies. Here we have a story the defies any easy definitions for concepts of corruption or conspiracy, heroes or villains, noble intentions or unconscious motives, legitimate knowledge versus invasion of privacy, liberty versus healthy limitation, ethical principle versus broader imperilment. The unlikely protagonist, an obsessed history professor, Dr. Arnold Potterley, seeks in his middle age to surmount finally the mediocrity that has dogged his career, He hopes to substantiate a radical theory about the Carthaginian civilization that would overturn the accepted historical view first promulgated by their enemies, the Romans(who had ultimately defeated them): that in times of duress, the Carthaginians resorted to child sacrifice. Dr. Potterley has unsuccessfully presented his case for years to obtain Government permission to use a highly regulated device called a "chronoscope" which enables people to look back in time through the manipulation of time-traveling subatomic particles called neutrinos. At the time of the story, Dr. Potterley's application is denied once again by the bureaucratic controllers of this technology. These same controllers continue (unintentionally) to tantalize this much-rejected scholar by publishing reports in its newsletter of the discoveries made by others who have managed to obtain such permission. It is now that our protagonist decides that he must find a way to take measures into his own hands, or otherwise live out the remainder of his life in depressive obscurity with his melancholic wife, Caroline, who also feels at loose ends in her own lonely world. At a faculty social function, Potterley chances upon a postdoctoral instructor in the field of physics, Dr. Jonas Foster, and though the new faculty member specializes in a subfield unrelated to the one governing the technology of the spectroscopy (which is called neutrinics), Potterley manages to progressively (though awkwardly) seduce the younger man into a sense of the ethical wrongness with regard to the Government monopoly upon such an important device for the cause of hisotrical scholarship, while also hinting at largely repressed sources leading to how it might be constructed through private initiative. Ultimately, Foster pursues the matter, not because he respects the history professor (whom he finds psychologically repellent in his single-minded zealousness), but because he deduces on his own that the field of neutrinics has been unjustly held back through Government regulation, leading him to conclude that this policy represents an assault on academic liberty. Employing his resourceful uncle. Ralph Nimmo, a well-connected science journalist, who helps him dig up the repressed findings of the inventor of the spectroscope and the field of neutrinics (who had died many decades ago in unwarranted obscurity). As these motely conspirators interactively pursue their secret and illegal project, Potterley, Foster, Nimmo and even Caroline find themselves lost in a technological and political labyrinth of errant corridors for their psyches, their careers and humankind as whole. The moral of the story lies in the question of whether or not if something is forbidden that it is always because of some petty motive of power, or if it is not sometimes because such legal constraint is actually a safeguard against actual ruination. Asimov has often been stereotypically written up in brief little biographical entries as lacking a depth of feeling for or range of understanding of human beings as complex individuals. This short story quashes such an ignorant and stupidly perpetuated viewpoint. Moreover, "The Dead Past" is by no means an exception to the ill-founded pronouncements of encyclopedists, as further exploration of Asimov's short fiction will prove to the honest reader. Asimov was a deep thinker in terms of both natural scientific and social scientific extrapolation, and the power of his stories arises from his compelling postulations of the future's potential scope of ramifications. The story under review may be most readily found in its latest appearance in publication: The Complete Stories: Volume 1. By Isaac Asimov. Published by Broadway Books. Copyright 1990.

Sunday, March 7, 2010

Review: "The Pi Man" by Alfred Bester

This nineteen-page short story is a "day-in-the-life" piece on an extraordinary individual, seemingly insane (at first), but actually rationally complex. It was first published in 1959, and written by a literary practitioner of rare output (in both senses of that adjective). Alfred Bester is the equivalent of the Japanese swordsmith when it comes to his middle-period short stories and novels: they are refined like the thousand-folded steel of a samurai sword that splits the spine of drifting feathers. This particular short story is no exception. What we encounter in the protagonist, Peter Marko, a dealer in currency exchange sales, is at once an obsessive-compulsive personality matched to a brain of genius. The tragedy for him is that he is far more than this. He is a super-sensitive: he can pick up patterns that no one else can perceive, cosmic wave patterns, demographic patterns, cultural patterns, mathematical patterns, absolutely everywhere he goes. Marko calls himself a "compensator", someone who must perform adjustments to restore balance wherever he is present. The problem is, the adjustments he must make sometimes compel him to go against his own moral make-up, which is why long ago he had chosen not to fall in love or form friendships. His genius enables him to create a self-soothing device that unfortunately draws the unwanted attention and suspicion of political entities and secret societies. This is because the device disrupts random and irregular wave patterns from the atmosphere and outer space, so that he can have a measure of peace at least within his own apartment. In this breathlessly paced short story in which we encounter many examples of word architecture that embody the complexity of Marko's thought patterns, the protagonist is compelled to fall in love despite his ethical ban on drawing good people into a world-view where love is particularly vulnerable in the face of more transcendent influences of an astrophysical nature. He also stymies the FBI, who fail to classify him as a spy or a nut. He leaves them with the enigma of the burdensome gift that defines his life: he is a "pi man": his awareness of reality is on the level of the mathematical figure of pi: the relation of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. In short, a cosmic truth impels him to act outside the normal behavior of less sensitive human beings, but his behavior can never obtain tranquility because that self-defining truth forms an insolvable paradox: the mathematical figure of pi, though it forms a stable proportion, goes into infinity. Beware that in reading Bester, we encounter a writer whose stories will pursue the revelation of a certain meaning of human existence with ruthless creativity alongside a jarring imagination and stinging humor. One can acquire this story in this most recent collection of his short fiction: Virtual Unrealities: The Short Fiction of Alfred Bester. Edited by Robert Silverberg, et al. Published by Vintage Books. Copyright 1997.

Saturday, March 6, 2010

Review: "Two Dooms" by C. M. Kornbluth

This short story was originally published in 1958, and can be classified as a science fantasy piece concerned with alternate history. Cyril M. Kornbluth is one of the most gifted short fiction writers one may encounter in the realm of speculative fiction, and this has to be one of his most brilliant works, though it runs only 34 closely-printed pages. Kornbluth uses a plot-device wherein he makes his central character ingest a peyote button administered by a Hopi medicine man. Our protagonist is an overworked, ethically-troubled young scientist, Dr. Edward Royland, working under Oppenheimer on the Manhattan Project in the desert of New Mexico. The peyote and a kind of quantum-shamanic ritual open a temporal portal for the protagonist, who is taken on an odyssey in which he experiences a far future America where the German Nazis and the Japanese Imperialists are the winners of World War II, and the feudalistic, fascistic, racist, and anti-intellectual tenets of these powers have been allowed to develop in the former United States, which these two powers have long ago divided between them in a kind of interlocking confederacy. The result of this has been a complete devolution of the free and democratic society the time-traveling young scientist had once known back in the mid-1940s. In terms of literary publication, this short story anticipates the same scenario found in Phillip K. Dick's brilliant novel, The Man in the High Castle, by six years, and in many ways Kornbluth's tale of an Axis Powers' victory conveys a far more intense experience for the reader in its exploration of the ramifications of both Asian and European versions of fascism upon the lot of the common person, as well as the wreckage it makes of education and scientific advancement. Kornbluth tells his story with great energy, mind-wrenching irony, accompanied by mounting implications of human depravity, startling humor, and a sense of human tragedy that leave the reader with a sense that this is tale is epic in scope despite its brevity. In the end it forces one to confront the fact that, that however terrible the invention of the atomic bomb remains for us, the failure to have developed it as a deterrent by the Allies against populistically-fueled militaristic movements might have led to an equally terrible fate for the ultimate progress and liberty of humanity across the globe. Kornbluth here also tears down the popular myth that Nazism attracted an unalloyed nexus of brilliant scientific intellects, for his story of an alternative future exposes the grossly unscientific notions and medieval presumptions of historical Nazi dogma and the absurd directions it would have taken humanity if it had developed unchallenged and become chronically institutional. To read this story one can perhaps most readily run across it in this most recent collection: His Share of Glory: The Complete Short Science Fiction of C.M. Kornbluth. Edited by Timothy Szczesuil. Published by NESFA Press. Copyright 1997.

Friday, March 5, 2010

Why Short Fiction?

We live in a paradoxical society of far fewer readers than preceding generations despite higher literacy rates. By "readers" I do not mean those who read only what is necessary to conduct business or what they might casually scan in a newspaper or website. I am also speaking only of adults and young adults, who read at no one's behest. More specifically, I mean those who read as a source of entertainment. Of these, an increasing number read only what is heavily supported by visual information (i.e., comic books and graphic novels). Most everyone else reads exclusively long fiction, or what we call most generically, "the novel". The reason for these trends, where an obvious link in the fictional chain seems to be largely missing from the lives of readers, can be laid at the feet of commercial publishing, which has determined choices through marketing to support their maximal profit-oriented motives. But if we look at fiction in its pure form of bringing imaginative pleasure to the human mind, then short fiction has a definite and important role to play. It is the form of fictional literature that is the most venerable. Some say the earliest surviving short story is "The Story of Joseph" in the the Book of Berashith in the Hebrew Testament. Others, using a different line of technical argument, believe it is more properly "The Book of Job", also from the Hebrew Testament. Be that as it may, the short fiction form compares very well with our species' much older oral tradition of storytelling that came before literature and co-existed with it until mass-produced industrial-scale publishing edged oral fiction out of the traditional picture. The fact of the matter is that short fiction, whether it be a prose poem, short narrative poem, flash story (vignette), short story, novella or novelette, possesses the potential of concentrated energy that can have a most striking effect upon the reader. Short fiction is also eminently suited to the pace of life in which we now find ourselves, where the time to read for pleasure can be very limited on any given day. Short fiction allows us to enjoy and focus on a rounded narrative in one, two, or three sittings, giving the reader a sense of imaginative accomplishment, and, indeed, something to fully reflect upon and about which he or she may converse with others. This blog will not discriminate on the basis of genre in its recommendations, and it will review matters in terms of positive points of reading pleasure. It will also not treat narrative poetry as a separate category from fiction; prose-form fiction is a relatively recent invention in literary history, so I will not commit the imbecilic presumption, say, of claiming that there was no "fiction" in English until Thomas Malory's prose romance, Le Morte D'Arthur was published in the middle of the 15th century! Hopefully the reviews and essays of this blog will serve to create a vital link in the chain to get publishers once again to print short fiction with the same dedication they did from the 1920s through the 1960s.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)