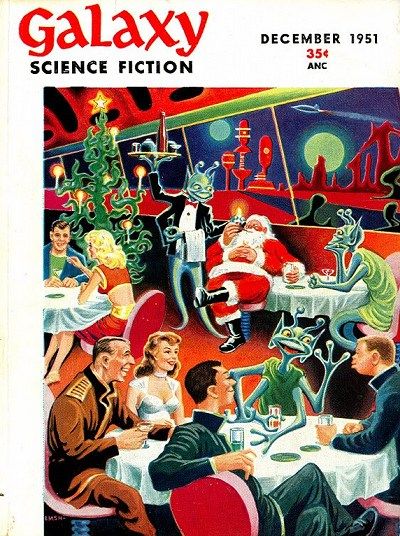

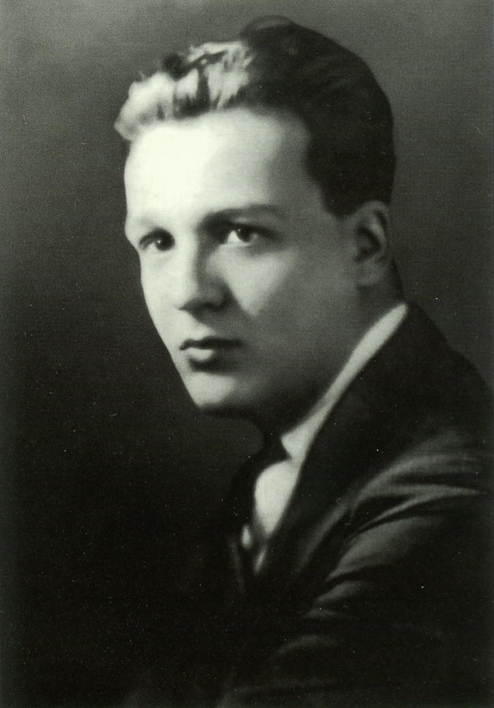

Comprising twenty-two pages, this novelette originally appeared in the August 1955 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. This tale explores several philosophical concerns whose specific permutations could only have arisen in our present technological age. Our relationship to machines, from Ancient times to the present, has always been to ease various burdens or onerous tasks of life, and soon thereafter to create greater uniformity and quality of products. More recently machines have been designed to solve problems of organization and order to maintain societal integration as human population densities have surpassed all previous norms. Machines have also been developed to make warfare more devastating and precise in its targets. Henry Kuttner projects all these uses of technology toward a logical future singularity of evolutionary unification whereby humanity surrenders its self-responsibility to computers and the robotic servants of higher artificial intelligence.

This may sound familiar, but in Kuttner's hands it has a different outcome than the typical science-fictional trope. In exchange for peace and stability, which the objective dispassionate synthetic mind of centralized planet-spanning computers can provide without error, humanity gives up self-governance. The computerized and wholly mechanized world supplies psychological satisfaction through virtual reality experiences transmitted by artificially induced trance states. All necessities are artificially manufactured and delivered as needed. Human society atomizes, as people become self-engrossed in personal whims and selfish pleasures. Machines exist only for humankind's physical health and egoistic pleasure. The moral compass of society loses its orientation as the need for struggle, competition, social discourse, human cooperation and emotional connection dissolve before computerized illusions of hedonistic and imaginative fulfillment. For this story, all this is already history. The author introduces us to a society that has just barely managed a slim generation ago to pull itself out of social implosion, by reasserting an active role in the material world. Human beings were failing to reproduce, because the underpinning social structures for basic human bonding had nearly entirely disintegrated. Faced with self-extinction, individuals came together to redirect the comprehensively mechanized-computerized world with a new fundamental program: enable human beings to become socially responsible again.

What these pioneers at rebuilding the mental construct of society face, however, is daunting: "conscience" itself has to be not merely re-learned but re-invented. The super-ego has to be reactivated. So in addition to dismantling technologies that provided for every comfort, pleasure and imaginative whim (so that human beings would be motivated to form social connections again with their fellows), negative reinforcement has to be introduced into a newly activated society that has been for so long in a technological womb of passivity. Here, Kuttner cleverly reinvents the mythological concept of the Fury in terms of a technological (and robotic) force of social control.

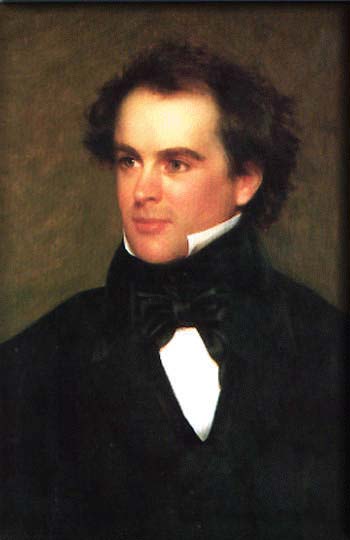

At this stage in the redevelopment of human society, people, while intellectually advanced, are still so morally infantile that murder is the essential form of moral corruption as people become re-accustomed to interacting with one another in complex ways. The title of the story is taken from a cryptic verse by Milton, who envisions that figure from Greek myth, the Fury, as a "two-handed engine at the door": the pursuing conscience of the person who mistakenly thinks he or she can escape the psychological implications of taking the life of another. In Kuttner's story, the Furies are robots that track down and follow those who have committed murder. The world is under pervasive sensory surveillance by a vast computer-mind maintained by a hierarchical human bureaucracy. An act of murder is inevitably discovered, and the perpetrator identified by the source of law and order: the wholly objective engine of artificial intelligence. The murderer then receives his or her Fury, a faceless, voiceless robot that follows them wherever they go, and keeps a vigil over them wherever they stay or rest.

These special robots will prevent their inmates from harming again, and at a carefully calculated moment, dependent on unknown factors of the individual, the Fury will execute the felon by any manner of assorted methods. The robotic Fury does not (and needs not) hinder the movement of its ward. This Fury of mechanical body can make of the entire world a prison for its charge, for the murderer can neither destroy it nor elude it. Its tenacious but serene accompaniment of its assigned felon is an example to all who observe the bizarre pair of the cost of taking the life of another: an act of harm, as the author points out, that cannot be practically undone.

In the story at hand, the supporting character, Hartz, a high-ranking administrator, induces a maladjusted citizen, Danner, into committing an act of murder, by demonstrating that he has the mathematical programming ability to undermine the normally unerring directives of the master-computer to impose the tenacious Furies upon guilty members of society. Hartz is a complex figure, despite not being the central character, for he believes in the moral rehabilitation of humankind so that it might not regress and lose its will to achieve character and reproduce itself. However, he is frustrated in being the penultimate controller. Hartz wants to be the master controller in this new alliance with the more perfect computerized/mechanized coordinators of human civilization. He still retains the regressed impatience of the id needing immediate gratification, and so, for all his sophistication of responsibility, he has not the restraint of desire found in a fully evolved human consciousness. The man above him, in short, is a mere hindrance, rather than a respected superior partner (in short, a recognized fellow human being) in the new project to rehabilitate humankind.

In the central character of Danner, Hartz sees a man even less evolved than himself, who can be persuaded to commit the very act that the institution to which Hartz belongs seeks most primarily to correct. As for Danner, he belongs to the last generation to enjoy the previous era of no psychological or physical challenges, and he lived long enough in that former reality to have it deeply imprinted on him. Thus Danner is incapable of fully embracing or finding higher satisfaction in the new reality, which requires effort and puts character-building limits on the boons of existence. Danner is deceived into believing that Hartz will use his hacking ability to derange the moral directives of the master computer, but Hartz knows that if he acts upon his knowledge, he will create a fault that may unravel the whole system of social control and thus humankind's general rehabilitation.

Despite his selfish ambitions, Hartz ironically has evolved enough to recognize that if he allows his faulty super-ego to have its way too far, it will ultimately defeat the purpose of the whole philosophical revolution to put a socially-responsible humanity back on its feet. So Danner ends up with a Fury as his constant silent companion, until the unknowable date when the robot will receive the algorithmic command from the central computer to destroy Danner. Yet Danner never succeeds in acquiring an inward sense of moral guilt, only an outraged resentment that his master-conspirator has somehow failed to protect him from the very fate that he had been guaranteed not to suffer. In return, he has gotten the promised unlimited source of wealth with which to pursue the pleasures Danner once knew in his youth before such things became rationed and contingent upon personal effort and social success. But where is the satisfaction when one is condemned to a mobile (though invisible) spot on Death Row?

Danner ultimately descends into murderous madness, as his unshakable Fury makes him an outcast even when his fellow human beings are willing to share his company, for his ubiquitous warden makes him attractive only to those who connect with him because of their superficial fascination with his impending doom. In the end, Danner seeks to slay Hartz, who can no longer put him off with promises to discover the reason for his failure to scramble the code of computerized justice and allow his minion to escape his punishment. At least he will have the double satisfaction of revenge and being put out of his misery afterwards by his mechanized jailor. Despite his efforts to temporarily separate himself from his constant attendant, the tenacious Fury still manages to prevent Danner from being able to kill again: that is, to murder Hartz. But Hartz does succeed in simultaneously killing Danner, just at moment the Fury foils his vindictive charge.

It is then that Hartz seeks to escape the same fate that befell the man of whom he made a dupe in his ruthless career designs. The very hacking code that he promised to use to deliver Danner from his sentence does indeed now save Hartz from sharing the doom of his morally clueless sap, the late Danner. However, the seemingly ruthless Hartz has by this point finally evolved just enough inwardly to have developed the fundamentals of a natural human conscience. At the end of the story, we come full circle, for we have the re-emergence in the mind of Hartz of the very psychological triggers that underlie the metaphorical construct of the Fury in Ancient Greek mythology. Thus the animated-metal symbol and imposer of afflicted guilt has been found disposable sooner than predicted. The flip side of Hartz (which is a nascent conscience) need not worry now over his cybernetic corruption of automated justice and its technological ramifications. If he is the first, he will not be the last to be pursued by the wholly mental-emotional construct of guilt -- now newly reinvented in him. He hears the footfalls of his Fury (a leitmotif in throughout the story), but there is no exterior robot to sound them. They fall within the silence of his mind alone. While this story may have been written fifty-seven years ago when the world still fundamentally operated by means of a clerk manipulating a filing cabinet, it feels intensely relevant and prophetic for the times in which we now live.

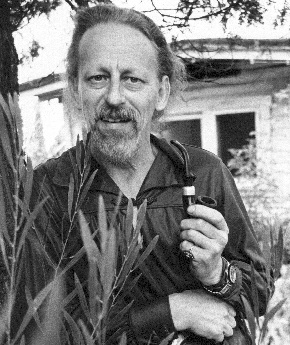

This tale may now be most readily obtained in this recent collection: The Last Mimzy: Stories, by Henry Kuttner, Del Rey Books, Copyright 2007.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Hi, Gandelyn,

ReplyDeleteAs an example of how biography and literature intersect: Henry Kuttner and his wife, C.L. Moore, studied literature and psychology at USC in the 1950s. I doubt that the young Kuttner could have devised a story like "Two-Handed Engine," grounded as it is in Greek mythology and the work of John Milton. Anyway, as I read your review, I couldn't help but think of the growing disconnection between people, who use a machine (which may not have two hands, but usually requires the use of two hands) as an intermediary in all things personal. High culture disdains science fiction, yet we live in a science fiction world. You can't comment on the state of the world without considering the ideas first formed by the lowly pulp fiction writer.

TH

Gandelyn,

ReplyDeleteIt's me again. In order to publish my previous comment to your blog, I was prompted to prove that I am not a robot by typing two nonsense words. That was the actual prompt: please prove you are not a robot. It won't be long before robots are smart enough to read and type those nonsense words. Then we'll have to outsmart them again. But for how long?

TH