Tuesday, March 9, 2010

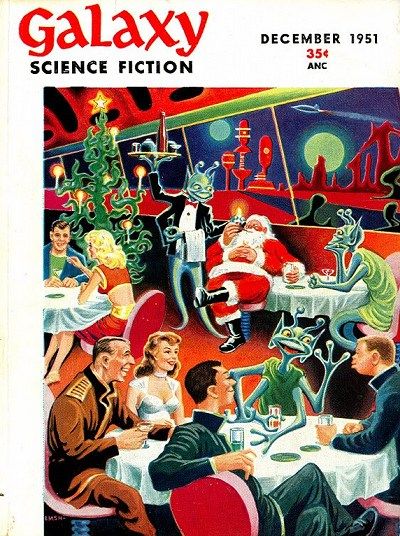

Review: "Parasite Planet" by Stanley G. Weinbaum

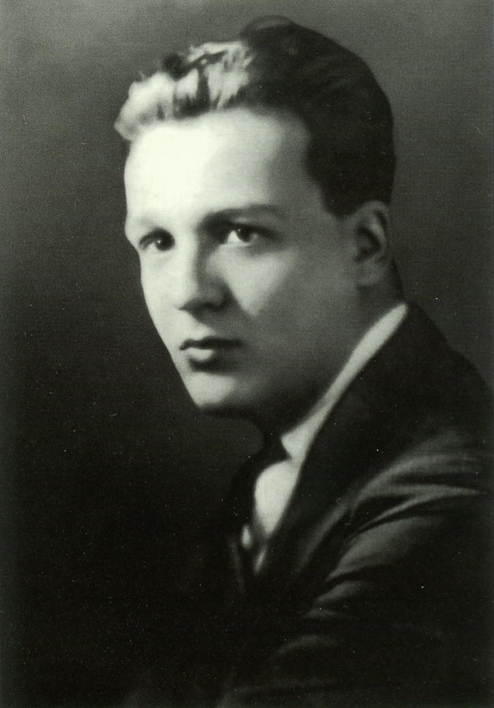

This story of twenty-eight pages was first published in 1935. During that era of speculative and fantastic fiction, tales tended to consist of headlong cartoonish action, unabashed anthropocentrism, cardboard character stereotypes, melodramatic language, slangy dialogue, unrealistic motives, naive assumptions about astrophysics and extraplanetary geology and biology, all topped off with uber-male chauvinism and melting females. There were rare exceptions to this pulpy ethos among writers of popular fiction, like H. P. Lovecraft for instance, but Lovecraft was more on the darkly weird end of the imaginative continuum. Front and center on the science fiction wavelength of the spectrum of fantastic literature stepped Stanley Grauman Weinbaum, who ripped through all those fictional tropes that the editors thought were sure-bets for periodicals sales, and introduced stories that science fiction fans had been hoping for but had only enjoyed as hints of possibility in previous writers. In a streak of incredible short stories and novellas written over a period of roughly two years, Weinbaum had fans cheering him on in the epistolary columns of the magazines. Then he died suddenly of cancer. But he was a signal light to a new generation of writers and editors, who realized they could write and published science fiction that picked up where Verne and Wells had left off, but in light of modern developments of psychology, physics, chemistry, and biological knowledge. Weinbaum's "Parasite Planet" is a perfect example of all that is best in the proto-revolution he mounted (it would have been his revolution to fully initiate right there in the mid-1930s if it had not been temporarily aborted by his untimely death). While this story takes place on a theoretical Venus that our modern space probes have proven cannot be, Weinbaum imagined his Venus in terms of the best scientific inferences at the time, and he built logically and vividly from there. However this point really doesn't matter in terms of the intrinsic value of the story tiself, for so keenly and thoroughly has Weinbaum thought out this planetary environment, that something like it must feasibly exist somewhere in this universe. Weinbaum posits the possibility of a planet whose heat, humidity and fecundity synergistically produce such biospheric super-abundance that life teems, thrives and feeds upon itself in a manner that makes the lushest rainforests on our own Earth seem like a static desert by comparison. All this highly active adaptation and counter-adaptation, hyper-competition and hyper-tropism results in an extremely dangerous and almost untenable environment for anything so fragile as a human being. And yet Weinbaum introduces to the reader a plausible adventurer who has pitted himself with ruthless intelligence and tremendous physical agility against this world in order to collect a rare native plant species whose medicinal properties can bring actual physical rejuvenation. If he can actually get his harvest of them off the planet, it will make him independently wealthy and fund his dream-projects as an engineer. The name of this intrepid go-getter is Hamilton "Ham" Hammond, and he is a tough yet latently compassionate American, occasionally trespassing across the British treaty zone of this imperially carved-up planet. The story is ingenious on many levels, among them its visceral portrayal of the struggle to survive against a seemingly endless array of rapacious molds, animal-like plants and human-like animals that can do everything from accelerating the entropy of any artificial structure to consuming life and limb with indifferent savagery; and all of this is vividly rationalized by the author in terms of biochemistry and instinctual behavior patterns. But the story gets better. There are others who brave this incredibly hostile environment, and we get to meet one as interesting as Ham: Dr. Patricia "Pat" Burlinghame, a cool yet latently sentimental British biologist studying in the field, cataloging the dynamically clever flora and fauna of this planet. If in the character of Ham, we encounter a skillful opportunist who is merely seeking a means to an end, in the character of Pat we encounter a woman who can match Ham in survival skills and practical athleticism, but who treks this planet for reasons completely the opposite of mercenary. She is an idealist for pure scientific endeavor: knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Ham is a fortune-hunter whose real interest lie far away from the hellish world in which he must abide for the nonce. When these two willful personalities cross-paths in this bewildering chimerical environment and amidst thisself-consuming ecosystem, they immediately fall into psychological and political conflict, despite the dangerousness of such a distraction when the world about them is hungrily pitted against them both. Slowly the urgent demands of practicality and survival compel them to set aside their differences and join forces to escape from the writhing overabundance of the hot zone of Venus obtain to the planet's more desolate cool sun-denied mountainous zone, where there is a pass leading to a protected colonial community. But first they must get past unforeseen, cryptic and inventively hostile bands of native protean sentient beings too intelligent to be deceived but too irrational to communicate with. So here is a story of convincing intellectual and physical equality and cooperation between the genders, leading to a mutual respect and understanding between two people that is hard earned but well earned. The psychologically-realistic dialogue exhilarates like a well-played tennis match, and the approaches of the two protagonists to getting out of scrapes in the most surprising scenarios is exhilarating. And all the while the enrapt reader is learning through pertinent facile descriptions and active contextual revelations the scientific ramifications of all these characters experience. Few writers have realized so much in novels ten times the length of this short story. The reader can most easily find this story from its appearance in this most recent collection: Interplanetary Odysseys. Written by Stanley G. Weinbaum. Published by Leonaur Limited. Copyright 2006.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment