Monday, March 8, 2010

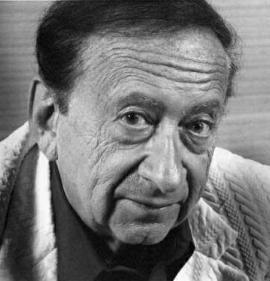

Review: "The Dead Past" by Isaac Asimov

This thirty-seven page short story was first published in 1956. It represents the provocative power of science fiction at its best, encompassing a dynamically balanced treatment of both a technical scientific theme and its depth of impact on a future human society. The plot of the story gradually but steadily weaves the two spheres of restless humankind and its half-blind creations into an accidental struggle with madness, as they interactively evolve in ways that cannot be predicted either by the original intentions of the scientific innovators or the reasonable presumptions of human psychology. New pathways lead to new ways to express or engender human pathologies. Here we have a story the defies any easy definitions for concepts of corruption or conspiracy, heroes or villains, noble intentions or unconscious motives, legitimate knowledge versus invasion of privacy, liberty versus healthy limitation, ethical principle versus broader imperilment. The unlikely protagonist, an obsessed history professor, Dr. Arnold Potterley, seeks in his middle age to surmount finally the mediocrity that has dogged his career, He hopes to substantiate a radical theory about the Carthaginian civilization that would overturn the accepted historical view first promulgated by their enemies, the Romans(who had ultimately defeated them): that in times of duress, the Carthaginians resorted to child sacrifice. Dr. Potterley has unsuccessfully presented his case for years to obtain Government permission to use a highly regulated device called a "chronoscope" which enables people to look back in time through the manipulation of time-traveling subatomic particles called neutrinos. At the time of the story, Dr. Potterley's application is denied once again by the bureaucratic controllers of this technology. These same controllers continue (unintentionally) to tantalize this much-rejected scholar by publishing reports in its newsletter of the discoveries made by others who have managed to obtain such permission. It is now that our protagonist decides that he must find a way to take measures into his own hands, or otherwise live out the remainder of his life in depressive obscurity with his melancholic wife, Caroline, who also feels at loose ends in her own lonely world. At a faculty social function, Potterley chances upon a postdoctoral instructor in the field of physics, Dr. Jonas Foster, and though the new faculty member specializes in a subfield unrelated to the one governing the technology of the spectroscopy (which is called neutrinics), Potterley manages to progressively (though awkwardly) seduce the younger man into a sense of the ethical wrongness with regard to the Government monopoly upon such an important device for the cause of hisotrical scholarship, while also hinting at largely repressed sources leading to how it might be constructed through private initiative. Ultimately, Foster pursues the matter, not because he respects the history professor (whom he finds psychologically repellent in his single-minded zealousness), but because he deduces on his own that the field of neutrinics has been unjustly held back through Government regulation, leading him to conclude that this policy represents an assault on academic liberty. Employing his resourceful uncle. Ralph Nimmo, a well-connected science journalist, who helps him dig up the repressed findings of the inventor of the spectroscope and the field of neutrinics (who had died many decades ago in unwarranted obscurity). As these motely conspirators interactively pursue their secret and illegal project, Potterley, Foster, Nimmo and even Caroline find themselves lost in a technological and political labyrinth of errant corridors for their psyches, their careers and humankind as whole. The moral of the story lies in the question of whether or not if something is forbidden that it is always because of some petty motive of power, or if it is not sometimes because such legal constraint is actually a safeguard against actual ruination. Asimov has often been stereotypically written up in brief little biographical entries as lacking a depth of feeling for or range of understanding of human beings as complex individuals. This short story quashes such an ignorant and stupidly perpetuated viewpoint. Moreover, "The Dead Past" is by no means an exception to the ill-founded pronouncements of encyclopedists, as further exploration of Asimov's short fiction will prove to the honest reader. Asimov was a deep thinker in terms of both natural scientific and social scientific extrapolation, and the power of his stories arises from his compelling postulations of the future's potential scope of ramifications. The story under review may be most readily found in its latest appearance in publication: The Complete Stories: Volume 1. By Isaac Asimov. Published by Broadway Books. Copyright 1990.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

It is more than something I read.As I read it, I feel it.

ReplyDelete