Sunday, April 25, 2010

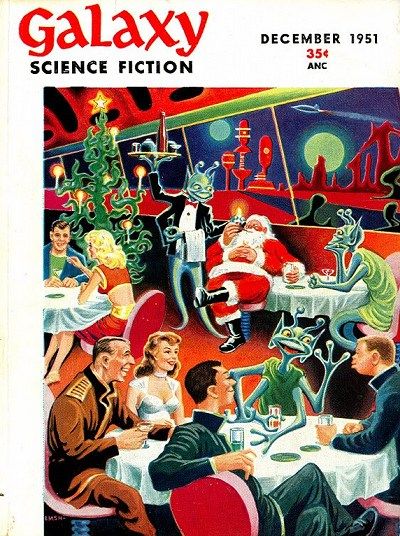

Review: "Shark Ship" by Cyril Kornbluth

This short story of thirty pages had its inaugural publication in 1958 under the title, "Reap the Dark Tide", but reverted to the author's original title when it was released in a posthumous collection of his works the following year. The year it first saw print was also the year Kornbluth died, and in 1959 was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Novelette. If there is any evidence that Kornbluth would have become a major author in his own right during the New Wave movement of the 1960s, this is a prime specimen. He, like Philip K. Dick and Alfie Bester were '50s writers ahead of the curve, but Kornbluth's untimely death prevented the full realization of the promise found in his short fiction and his collaborative novels with Frederick Pohl. It cannot be doubted that the 1960s would have brought his creative genius to full fruition, due to the truly expansive editorial and imaginative parameters set by that boundary-pushing decade of intellectual ferment. This particular story finds him in exceptional form, and shows he died at a time when his writing was attaining a new level of ambition. What we have in this tale of deceptively simple yet subtly ironic title, is a work that could have been turned into an epic science fiction novel. His research into nautical engineering, meteorology, oceanic currents, marine ecosystems, population control dynamics, and sociopolitical organization is pieced together in brilliant narrative form, and his extrapolations therefrom into a future, self-sufficient, sea-bound, human society conveys intense plausibility. For such a society to exist wholly independent of land resources, he paints a culture of hyper-organization as ruthlessly efficient as an ant colony, constantly following the algal blooms that spawn the greatest harvests of the world's seas. Maintenance of one's means of survival is paramount, since these groups may never return to land to obtain replacements. It is war of watchfulness, industrial scale recycling and meticulous brigade-form policing against oxidation. Every member of society performs a task intrinsic to the success of the whole. Kornbluth eschews the temptation to paint a dystopian one among these marine-bound humans, who have an equally strong sense of humanity tempering their iron-willed commitment to sacrifice for the greater good when necessity demands it. Their government is a representational democracy, bound by legal limits based on purely practical considerations. His world-building in terms of these seafaring folk paints a noble and convincing picture of collective ingenuity and service over self. This is not to say there is not a dystopian presence in this tale of a future Earth of riven populations. It is the world of land-dwelling humans, which has become an utter mystery to those descendants of the humans who generations ago volunteered to alleviate population pressure by voluntary exile to the sea. One of the ships in one of several tribal fleets suffers the fatal mishap of losing its net in a sudden squall, though the captain does succeed in preventing the ship from capsizing. There are no spare fibers from the rest of their parent fleet from which they might make another. Though they freshly retain their share of a great marine harvest that may feed them for several months yet, they will never be able to participate again in such ventures. After being abandoned by the rest of the fleet as a matter of their ancient code of collective survival, they choose (rather than opting for the traditional mass suicide to avert the ultimate resort of cannibalism) to reconnoiter a navigable place of land to seek material to make a new net. Such a decision is tantamount to breaking an age-old agreement with the land-dwellers against making any such move as an act of trespass in spheres now determined to be mutually inviolable. The scout team discovers that the landed side of humanity, though it was the fount of the civilization from which their own sea-going one sprang, has become something very odd indeed. Just as the sea people developed a highly disciplined and honor-bound culture over the generations to cope with the harsh rules of the sea and the requirement to be totally self-sufficient, the land people had developed their own means of coping with the problem of overpopulation and limited land resources. I will not reveal the terrible truth, but suffice to say, it rests with this single transgressive ship to take the lead in saving the idea of humanity and creating therefrom a viable civilization for the future of the planet. What haunts the mind is the prophetic quality in Kornbluth's revelation of the landward half of humanity. Many aspects of today's popular media culture are pointing in the direction he reveals in the evolutionary psychology of the land-bound folk. Where cooperative solutions fail, where does increasingly desperate competition for resources lead the collective mind of a society originally disposed toward mercy but which atavistically views such a humane disposition as a maddening burden? As with all my Kornbluth recommendations I point you to the following volume put out by the commendable efforts of the New England Science Fiction Association: His Share of Glory. Written by C. M. Kornbluth. Published by NESFA Press. Copyright 1997.

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Review: "The World Well Lost" by Theodore Sturgeon

I ran across one comment by a fan that Sturgeon can be reckoned the greatest short story writer of the 20th century. Such hyperbole is forgivable, even among those of us who realize that such a thing could never be quantified. Sturgeon is great-- though he is himself dead, his writing is not a "was" but remains vibrant for anyone living now who discovers what he left behind for us. Sturgeon needs to be esteemed in this age that otherwise prizes puerile writing, when writers of his caliber are all but forgotten even among those who consider themselves "readers". This review will consider another of those short stories that seem "miraculous", and one that is vintage Sturgeon. It runs across nineteen pages, and covers more emotional, scientific, sociological, psychological, anthropological, political and philosophical territory than most series of novels do today weighing in at five-hundred pages per volume! And did I mention that the four main characters in this tale are utterly fascinating, and that the central character is utterly surprising? Before I summarize, let me just say this: if you have at least a workable lump of humanity on your mental potter's wheel, this story has the power to enable you to recognize spiritual kinship with someone you thought completely different from yourself. In short, it can turn ill-informed bigots (i.e., bigots who are so not because they like to be but because they have been brought up wrong), into sighted souls who realize the alien is not other but beloved self. This story first came out in 1953, and it was far in advance of many of the enlightened components of the counter-cultural movement that crystallized over a decade later. Indeed, recognizing that much of what that counterculture achieved for us in expanding our moral breadth has been undone in more recent decades of resurgent conservatism, there are few writers who can say with greater beauty and insight what Sturgeon said here in this tale, now almost sixty years ago. Okay, it's science fiction, but back in his day, science fiction writing (not the "B" Hollywood movies) was the place where some of the greatest explorations of the meaning of life were being imaginatively made, and Sturgeon was among the cream of the crop not merely as an idea man but in sheer writing skill. So in this story we have a couple aliens land on the Earth and make of themselves benign and appreciative visitors, who obviously are looking to find some niche where they can make a home for themselves. These two beings appear to be a mated pair, and have physical characteristics that resemble the most beautiful aspects of both birds and humans. They also emanate a love so morally appealing that it captures the imagination of the world, whose fascination is exploited commercially to the hilt. At this time in Earth's future history, humanity has resolved itself into rather focused forms of sensory exploration, the social castes being purely practical: a majority are consumers of sensation, a minority are creators of sensation, and an even smaller minority are the actual "doers" who make the machinery and conveyances of society function and perform. The two alien visitors, nicknamed "the loverbirds" by the media, are our first two main characters. However, the people of Earth soon learn that this pair of lovely visitors are fugitive criminals from a planet ("Dirbanu"), which many years before had established a policy of "no relations" with Earth after one accidental discovery by a Terran ship, and a single ambassadorial mission from that planet with a disappointing lack of rapport. Indeed, their planet is shielded with an unknown technology that not only prevents any one from landing on it, the shielding also blocks all scientific or espionagic ability to discover its nature. The culture of this future Earth, however, is mad to acquire any technological prowess which it itself lacks, and so the government of Earth is only too willing to cooperate with Dirbanu's request that the fugitives be extradited back to them; for the government of Earth hopes that, in so cooperating, it might ingratiate itself for some form of scientific exchange program. Now we come to our next set of main characters, Captain Rootes and Midshipman "Grunty", of whom the latter shapes our perspective for the remaining course of the story. These two men are recruited to form the crew for the spacecraft capable of speedily deporting the two fugitives, whose ability to be in any way criminal is nowhere evident to the perceptions and sensibilities of Earth people. Rootes and Grunty, both members of the "doer" caste, are at this point highly noted for their superior quality of teamwork and handling of space travel, and hold a perfect record in the discharge of all previous assignments. Both are loyal to their work and each other, though they are of surprisingly different personalities. This difference appears to be complementary however, and the government of Earth sends them on their strange new mission with complete confidence. Rootes, for all his professional competence, is a self-dramatizing, super-heterosexual, who is nevertheless unfulfilled in actually establishing a meaningful loving relationship among his endless round of romantic conquests whenever he is in port between missions. Grunty, who is so named for his extreme level of laconic expression, has a rich inner life, evidenced by his erudite and sophisticated reading material, a library that he transports with him on all his missions. It is also evidenced by the omniscient narrator's progressive focus on his mind, which has a richness of expression, despite the fact that it is never given utterance. The crisis arises however, when the two convicts in their transport evidence signs that they can read Grunty's profound and poetic philosophical thoughts, especially when he directs them sympathetically toward them. The problem is, Grunty does not want anyone to know of his inner life, which is not only his chiefest treasure, but his very means of sanity in terms of its privacy. The aliens they are deporting are highly sympathetic to his inner nature, but this is not enough for Grunty. The fact is, there is the probable threat that they will telepathically convey the nature of his inner life to the rest of their kind, and then this will possibly be revealed to his fellow Earthlings as relations form between the two planets, and it is with his fellow human beings that Grunty definitely does not wish to share these precious thoughts and feelings. Matters complicate from there, but it turns out in no way you might suspect. The ending has two parts; both are surprising, both are wonderful. I will reveal no more than that the ramifications of this story's ultimate revelations are something people in America badly need to understand today, in terms of learning to let go of our culture's special knack for needlessly persecuting certain social groups. This tale may most readily be found in the following recently published book: The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon, Volume VII. Published by North Atlantic Books. Copyright 2002.

Thursday, April 15, 2010

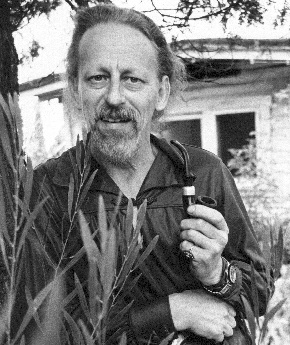

Review: "With These Hands" by C. M. Kornbluth

First published in 1950, this short story goes thirteen pages and has all the perfection of a Greek tragedy. The protagonist, Roald Halvorsen is a sculptor and painter living in a not-to-distant a age (vis-a-vis the mid-twentieth century when the story is written -- in fact it has nearly fully arrived in our own time of 2010) where technology and low-brow tastes have almost wholly supplanted the traditional visual and plastic art forms of centuries-long development. Art is now the product of computerized mathematical calculations fed into precision-guided machines operated by tech-school manipulators. The calculations themselves are based on based on composited data drawn from demographic subliminal surveys that determine various ratios for strategic factors of appeal. Under this reality, Roald Halvorsen just barely makes a living as a freelance art teacher living in a studio at a slum district of the city. At the beginning of the story, his final hope for a commission is dashed, when his last significant patron, a local diocese of the Catholic Church, finally relents in its conservatism, and gives over to the new form of computer-synthesized art. For Roald, this is the final dejection of his stubborn dreams, though he has not yet fully processed the life-long ramifications of this pivotal failure until toward the end of the story. In the meantime, he encounters a new student, a woman tentatively attached to a wealthy astronaut hero who has explored Mars, and is preparing for an expedition to Ganymede. While her husband as a dilettante's curiosity for "real" art, especially as a quirky survival in their super-technological age, she is genuinely interested in developing artistic skills for her own personal creative development and satisfaction. Roald realizes after the first interview and in the aftermath of the first class lesson, that she is attracted to him and that, moreover, he has fallen in love with her. However, he has reached the middle-age of experience, and is too canny to deceive himself any longer as to where such an affair will lead. He will be loved for the wrong reasons, because he is a talented man of sincere passion who is pitiable for being born too late and into a world that places no remunerative value on anything genuinely authentic. In short, he realizes that a close relationship with another human being is as terminal as his hope to maintain an existence as a real artist. Otherwise he can look forward only to worsening cycles of malnutrition and minor spells of temporary relief from such circumstances as the whimsy of a minority of the public takes a quaint interest in the world of real art he so stubbornly holds onto. He admits to himself that the world of the computerized professions is too boring for his sensibilities to pursue. In the end, he makes a pilgrimage to an isolated masterpiece of magnificent public sculpture that borrows from all the ages of artistic endeavor. It has managed to survive a nuclear war from some years before, but is now situated in a no-man's-land of irradiated Denmark. It has been Roald's dream to see it in person one day. Finally he arrives at the right set of convictions to make that journey, which solves all his problems in a way both poetic and poignant. This story embodies psychological realism at its best, and its central character appeals to reader both for his aesthetic principles and his self-understanding. This could have been scripted into an Emmy-award winning Twilight Zone episode. As it stands, it deserves to win a Retro-Hugo for Best Short Story of 1950. Kornbluth may be better known for other stories, but I think this was a highly personal piece. The doomed determination of Roald Halvorsen is highly prophetic of Kornbluth's own fate later in the decade. The collection to find it in is: His Share of Glory. Written by C. M. Kornbluth. Published by NESFA Press. Copyright 1997.

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

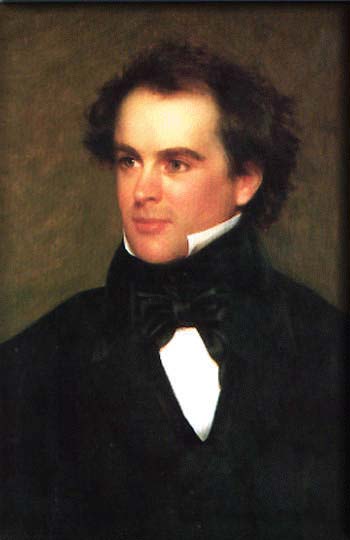

Review: "The Whisperer in the Darkness" by H. P. Lovecraft

This fifty-seven page story first saw publication in 1931. Howard Phillips Lovecraft was the definite successor to Poe, Hawthorne, Chambers and Bierce in the American tradition of weird fiction, but people often forget that he blended his weird fiction with science fiction. This story is no exception. It is my fourth favorite of his stories (my first three being: his novella, The Shadow Out of Time, his novella, The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and his short story, "The Colour Out of Space"), and I only place his short story, "The Dreams in the Witch House", as more frightening. I review it here because it does not get the attention it deserves next to his other great works of the so-called Mythos Cycle, such as "The Call of Cthulhu" and "The Dunwich Horror" (two very fine fictional pieces in themselves, no doubt). However, "The Whisperer in the Darkness" has a focus, plot complexity, tension and character development that is remarkable. It weaves together historical incidents (which were recent at the time Lovecraft was writing it in 1930 (i.e., the devastating Vermont Floods of 1927), with New England folklore from both European settler and American Indian traditions, and the author's own imaginative development in terms of fantastic detail and scientific, syncretic rationalization of superstitious beliefs about the mysterious qualities of remote hill country. Our central protagonist and first-person narrator is a professor of literature at the Lovecraft-invented Miskatonic University in Arkham Massachusetts, Dr. Albert Wilmarth. Yet here we also have a secondary protagonist with whom Wilmarth has a suspensefully tenuous through sincere and mutual connection: Henry Wentworth Akeley, a retired professor and scholar of Vermont folklore, who has recently returned from his campus-based career to spend his remaining days on the lonely farm he inherited from his forebears, situated at the foot of Dark Mountain, and with the closest community being some miles away in Townshend, Vermont. The two men discover each other when Akeley responds to an article picked up by the regional newspapers quoting Wilmarth's viewpoint on strange corpses of unknown species reportedly washing up or floating by during the floods. Wilmarth is a skeptic, though sympathetic to the traditional rural imagination as a pleasant curiosity of which he himself as a known antiquarian interest. Akeley sends Wilmarth a personal letter of scholarly and well-reasoned content that argues against the skepticist position on the matter, by revealing details of recent personal experience that point to an even more complex reality behind those purported remains of unlikely nature. Wilmarth recognizes the quality of a fellow intellect in this letter of introduction, and intuits that Akeley may not be mad, even if his powers of reason have taken the wrong track. A healthy correspondence begins, but after certain items of physical and recorded evidence are mailed to Wilmarth from Akeley, their communications begin to be disrupted, and even invaded by a third party. What is particularly creepy about this story is that Lovecraft presents us with human agents working for extraterrestrial intelligences, but the motivations of these individuals for forming such alliances is not quite known, and can only be partly surmised from certain cosmic revelations at the end of the story. These agents behave in a fascinating variety of ways that are not quite right in their determination to pass for normal, though they are obviously committed to preserving the secrecy of the activity of their alien masters. Akeley manages to get enough through to Wilmarth that his presence at the old farmhouse has aroused the displeasure of an unknown race dwelling in the remotest heights and dingles across Vermont's Green Mountains. Akeley suffers increasing harassment of a bizarre nature at night, which is now escalating to threats of invasion of his home, if not for the presence of self-martyring watchdogs and the reports of a gun Akeley has purchased to direct at the sources of strange sounds and voices coming from the nearby woods. The insidious nature of the non-human voices and the disturbingly indefinable noises associated with them (not to mention the fatal harm done to his kennel of dogs by each morning) makes this solitary old man of otherwise peaceable disposition feel quite justified in his use of violence. In the meantime, the human agents begin to mysteriously suborn other people so that they are able to intercept the mailings between the two scholars, and begin to impersonate Akeley in subsequent letters to Wilmarth. The literature professor, however, is not wholly deceived, though a part of him does not like admitting the implications of such an impersonation. Despite reassurances from the pseudo-Wilmarth, there is also a rather strident request that the physical evidence be mailed back to "him", even though originally Akeley had declared that they were to remain in Wilmarth's safekeeping. Wilmarth decides that his friend by correspondence must now be in grave danger, whether it be from some sapient alien species or simply from some strange secret society of mere human beings, and so he makes arrangements to finally visit Akeley, even though he realizes at this point he must do so through these weird middlemen. The rest I leave the reader to discover, though I will say that if any think it will lead to a supernatural explanation, guess again. The science fictional element carries the climax and resolution of the story, but fascinating and dreadful mysteries remain after the story ends, and this tale is no less frightening for not being supernatural or even wholly evil in terms of the nemesis. The antagonists have purposes as practically alien to human moral motivations of good and evil, as they are biologically alien to our world's biosphere. This is a rich reading experience, and I am happy to report that the Howard Phillips Lovecraft Historical Society is completing work on an accurate and evocative feature film version of this fictional work. This story may be most cheaply obtained in this authoritatively edited and superior collection that has remained steadily in print to the present: The Best of H. P. Lovecraft. Written by H. P. Lovecraft. Published by Del Rey. Copyright 1987.

Sunday, April 4, 2010

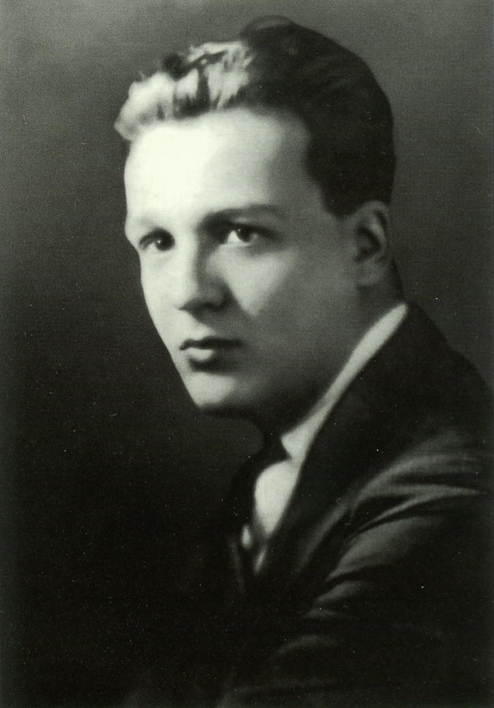

Review: "The Man Who Lost the Sea" by Theodore Sturgeon

First published in 1959, and running a mere eleven pages, we encounter in this short story a mysterious situation, strange refractions of a confused perspective that only slowly reveals its true nature. What thoughts occur to one who is injured, dying and mentally confused by physical trauma disrupting rational faculties? What shapes of thought form as perceptions of reality, subconscious fantasy and composites of both trade places as a man's consciousness shifts from one level of quality to another? What of a man who began with simple dreams playing with scientific models of vehicular flight, and then later, underwater forays of exploration whose dangerous experiences and human comradeship endowed a youth with the character to explore realms far more remote, and using flying machines far more complex than the models he had once constructed and played with on the seashore back in his childhood home. A man in the confused place between life and death constructs a delusional landscape, and imagines the same sea before him that raised him. It is only in the essential clarity of his dying moment that all is made clear both for the reader and the protagonist: an astronaut has crashed on a lonely world whose desert may or may not have been once a sea, but was for awhile a sea again in the mind of the mortally injured explorer, the only member of the crew to survive, if only for a day. And the shallow quicksand in which he lay buried up to his shoulders, for a time, was merely part of the beach peopled by the former selves which had progressively led him to take this trip to a foreign planet, but for whom now he has no patience in terms of what he temporarily deems as childish curiosity leading step by step to an adulthood fate of folly. In the end, the timing of the orbit of the satellite he has observed in his state of indisposition is not the same as the one he had watched for in the night sky of his youth, and it is this penetrating deduction that cracks open his understanding of what lay behind these frustrating delusions of his earlier selves as separable beings, playing on the beach to better visualize the potential of the technology for which his toys are accurate models, and later, at an intermediate stage of aspiration, out adventuring as a scuba-diver along that same coastline, thereby acquiring the psychological fusion of cooperative team identity. Yet suddenly after a day of careful observation, he realizes that the satellite passing above him is not the artificial work of man, but the natural satellite known to astronomers as Phobos. He is actually not at home on the blue Earth, but crashed without hope of return on Mars. And yet in his last flash of recognition at the hopelessness of his situation, it occurs to him that he, his presence there, represents a miracle. From the wreckage he crawled, he has lived long enough to recognize humankind's achievement: we (humankind) have finally made it to Mars! In this brief though engaging short story of skewed, frustrated and fragmentary perceptions and jumbled, superimposed memories, we encounter a writer whom other writers can love, if for nothing else than the sheer artfulness of his conveyance of story. Here we have a man who writes with a verve of sly purpose that will not only surprise you but clutch at your heart and awaken a forgotten nuance of humanity ready to emerge from your ancestral chest of profounder emotions. This story has been most recently and authoritatively collected in: The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon, Volume X, Written by Theodore Sturgeon. Published by North Atlantic Books. Copyright 2005.

Saturday, April 3, 2010

Review: "Worms of the Earth" by Robert E. Howard

Comprising forth-six pages and first published in 1932, this work represents a chief component in a series of stories Robert Ervin Howard wrote over a period of perhaps seven years concerned with a Pictish king living amidst the height of Roman power during that empire's expansion through the Island of Britain. It is a work of well-researched historical fiction, but much more. It is also a work of well-researched folklore, beautifully rationalized by Howard's scholarly and imaginative mind. So a little background for those less initiated with ancient history. The Picts were the first historically recognized inhabitants of a region we now call Scotland, but which in Roman times was called Caledonia. The Romans once briefly held nominal control of the Lowland region of Caledonia, when they built the palisaded earthen defensive structure called Antonine's Wall. But they soon had to pull back, and they dug in at a more permanent stone construction which survives to this day called Hadrian's Wall. This is to go a long way to say that the Romans never conquered Caledonia (or, if you prefer, "Pictland"). Howard's hero of his Pictish cycle of stories is a king he called "Bran Mak Morn". This character represents the energetic cleverness, the iron-will, the contempt for wealth, and the dedication to honor, duty, courage and self-sacrifice, which the nobler Romans (as for instance the Roman historian and ethnographer, Tacitus) admired in certain of their barbarian foes, including the obscure quasi-branch of the Celtic family known as the Picts (meaning, "Painted People", because they painted their bodies with pigment from the woad plant in mystical designs for religious rituals and for warfare. Howard portrays the psychology of the people of those times, cultures and situations with uncanny accuracy, and his use of historical detail is deft, fascinating and never obtrusive in terms of the flow of the story. To read Howard in such well-conceived stories as these is to wonder that he may have discovered a lost source that fits the disjointed fragments of history into a dynamic whole. This story, like all his tales of Bran Mak Morn, puts the reader in media res, and at yet another juncture where the arrogance and oppressiveness of Roman intrusion into a once happily isolated barbarian milieu drives the Pictish king to new heights of frustration. He has fought them at many times and in may ways, and the Romans would love to parade him through the streets of Rome in a cage in chains for a triumphal parade, but King Bran is elusive and crafty. At the beginning of the story he poses as a mere emissary of the Picts, with whom the Roman Governor, Titus Sulla, stationed at the Roman provincial seat of Eboracum in northern Britain, would love to pacify in the interest of stabilizing profitable (and taxable) commerce between the two peoples. Bran is wined, dined and bedded with paganly civilized Roman hospitality, as they would any aristocratic representative of a foreign nation with whom they want to deal. Yet Bran Mak Morn, as his own spy of kingly purpose, observes only how the Romans treat the common people from among his bartering Picts with unfair dealing in the market and no justice in the Roman civic courts of law, and sadistic severity in terms of legal punishment for any rebellion against such ill treatment. Sulla, the governor, exemplifies the most heinous tendencies that may crop up in the Roman characteristics for self-assurance and self-congratulation. In Sulla, the confidence of a triumphant civilization has grown twisted into hatefully contemptuous attitudes toward the Picts, for whom he constantly betrays a view that they are somehow less than human. Yet Bran knows that Sulla is no fool, and that his power makes him untouchable by any means at the barbarian king's mundane disposal. This is where the story turns onto a note of ingeniously rationalized folklore, and also, consequently, becomes a work of weird fiction. Howard knew of many obscure tales of yet an earlier race inhabiting Britain, before the even the Iberic and Celtic settlers (of whom the former Bran's royal dynasty has in pure genetic form). These were the Neolithic peoples that built the menhirs and dolmens: the outdoor temples of standing stones and post and lintel stones, arranged in circles or lines. Howard weaves into this story the revelation of what became of this race, which according to the scholars of his day, was a mystery. Yet the legends of the British Isles spoke of a diminutive folk, a different species of human, whom the arrival of true homo sapiens had driven into an underground existence. In Howard's tale, they are a lost subterranean race, who have adapted to the darkness beneath the earth, and have physically evolved in fearsome ways, even as they have built a vast and complex world of interconnected caverns and cave tunnels with stone-sealed crypts set in marsh-bound mounds and narrow mountain crevices, each leading to precipitous stairwells of eerily shallow steps, much worn by sheer millenia of years in their use. Through the mediation and guidance of a half-elfin witch, called Atla (who exacts a surprising yet sympathetic toll), Bran finds a way to bargain with this lost race his own forebears had once driven into their bitter troglodytic existence. Through their subtle and insidious reach, he knows they can capture the one man at the top of the provincial Roman pyramid, whom Bran could never otherwise touch, even on the field of battle. It is Bran's hope that these literally subhuman creatures may bring him Sulla, the man who dares treat his own people as subhuman. Then he might actually be able to fight Sulla man to man, and teach the Roman governor what honorable justice is. Yet this is no tale of unalloyed triumph, and I will leave it to the reader to discover the ironic twists of its plot. I will only mention that the narrative voice of this story has a powerful cadence like that of an epic song, and he sprinkles it with concise images evocative of ballad metaphor. Howard was a rare bird, for he tells his best tales as though he is an ancient bard who knows nothing of Christian civilization's deeply embedded habits of ameliorating the echoes of the primordial barbarian imagination. In terms of Howard's art, the reader is taken back with astonishing clarity to the days when such legendary heroes as Beowulf lay as yet untouched by the transfiguration of the monkish quill. This story has been most recently published in the following collection, compiling the author's entire cycle of short stories, poems and essays devoted to this protagonist: Bran Mak Morn: The Last King. Written by Robert E. Howard. Published by Del Rey Books. Copyright 2005.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)