Sunday, April 25, 2010

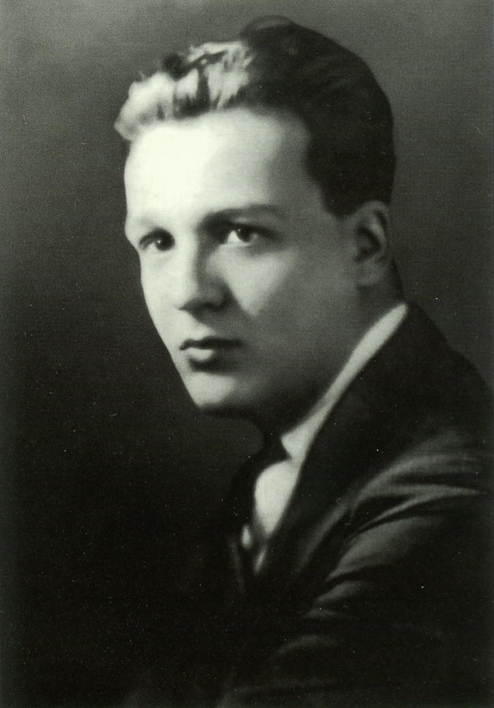

Review: "Shark Ship" by Cyril Kornbluth

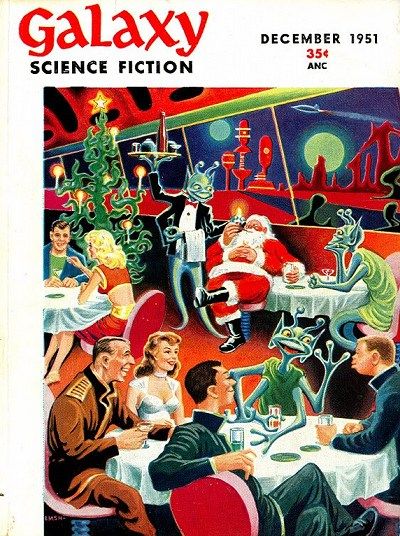

This short story of thirty pages had its inaugural publication in 1958 under the title, "Reap the Dark Tide", but reverted to the author's original title when it was released in a posthumous collection of his works the following year. The year it first saw print was also the year Kornbluth died, and in 1959 was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Novelette. If there is any evidence that Kornbluth would have become a major author in his own right during the New Wave movement of the 1960s, this is a prime specimen. He, like Philip K. Dick and Alfie Bester were '50s writers ahead of the curve, but Kornbluth's untimely death prevented the full realization of the promise found in his short fiction and his collaborative novels with Frederick Pohl. It cannot be doubted that the 1960s would have brought his creative genius to full fruition, due to the truly expansive editorial and imaginative parameters set by that boundary-pushing decade of intellectual ferment. This particular story finds him in exceptional form, and shows he died at a time when his writing was attaining a new level of ambition. What we have in this tale of deceptively simple yet subtly ironic title, is a work that could have been turned into an epic science fiction novel. His research into nautical engineering, meteorology, oceanic currents, marine ecosystems, population control dynamics, and sociopolitical organization is pieced together in brilliant narrative form, and his extrapolations therefrom into a future, self-sufficient, sea-bound, human society conveys intense plausibility. For such a society to exist wholly independent of land resources, he paints a culture of hyper-organization as ruthlessly efficient as an ant colony, constantly following the algal blooms that spawn the greatest harvests of the world's seas. Maintenance of one's means of survival is paramount, since these groups may never return to land to obtain replacements. It is war of watchfulness, industrial scale recycling and meticulous brigade-form policing against oxidation. Every member of society performs a task intrinsic to the success of the whole. Kornbluth eschews the temptation to paint a dystopian one among these marine-bound humans, who have an equally strong sense of humanity tempering their iron-willed commitment to sacrifice for the greater good when necessity demands it. Their government is a representational democracy, bound by legal limits based on purely practical considerations. His world-building in terms of these seafaring folk paints a noble and convincing picture of collective ingenuity and service over self. This is not to say there is not a dystopian presence in this tale of a future Earth of riven populations. It is the world of land-dwelling humans, which has become an utter mystery to those descendants of the humans who generations ago volunteered to alleviate population pressure by voluntary exile to the sea. One of the ships in one of several tribal fleets suffers the fatal mishap of losing its net in a sudden squall, though the captain does succeed in preventing the ship from capsizing. There are no spare fibers from the rest of their parent fleet from which they might make another. Though they freshly retain their share of a great marine harvest that may feed them for several months yet, they will never be able to participate again in such ventures. After being abandoned by the rest of the fleet as a matter of their ancient code of collective survival, they choose (rather than opting for the traditional mass suicide to avert the ultimate resort of cannibalism) to reconnoiter a navigable place of land to seek material to make a new net. Such a decision is tantamount to breaking an age-old agreement with the land-dwellers against making any such move as an act of trespass in spheres now determined to be mutually inviolable. The scout team discovers that the landed side of humanity, though it was the fount of the civilization from which their own sea-going one sprang, has become something very odd indeed. Just as the sea people developed a highly disciplined and honor-bound culture over the generations to cope with the harsh rules of the sea and the requirement to be totally self-sufficient, the land people had developed their own means of coping with the problem of overpopulation and limited land resources. I will not reveal the terrible truth, but suffice to say, it rests with this single transgressive ship to take the lead in saving the idea of humanity and creating therefrom a viable civilization for the future of the planet. What haunts the mind is the prophetic quality in Kornbluth's revelation of the landward half of humanity. Many aspects of today's popular media culture are pointing in the direction he reveals in the evolutionary psychology of the land-bound folk. Where cooperative solutions fail, where does increasingly desperate competition for resources lead the collective mind of a society originally disposed toward mercy but which atavistically views such a humane disposition as a maddening burden? As with all my Kornbluth recommendations I point you to the following volume put out by the commendable efforts of the New England Science Fiction Association: His Share of Glory. Written by C. M. Kornbluth. Published by NESFA Press. Copyright 1997.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Wonderful review. We need more reviews like this about Kornbluth's work.

ReplyDelete