Sunday, April 18, 2010

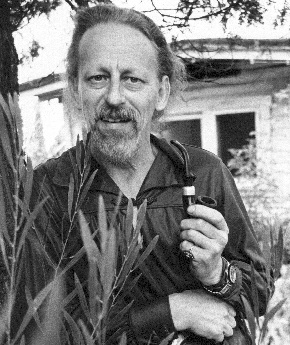

Review: "The World Well Lost" by Theodore Sturgeon

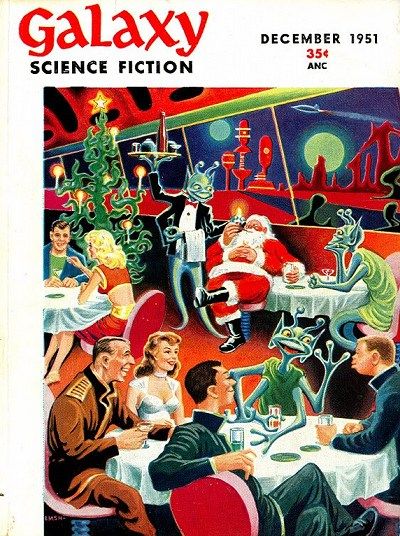

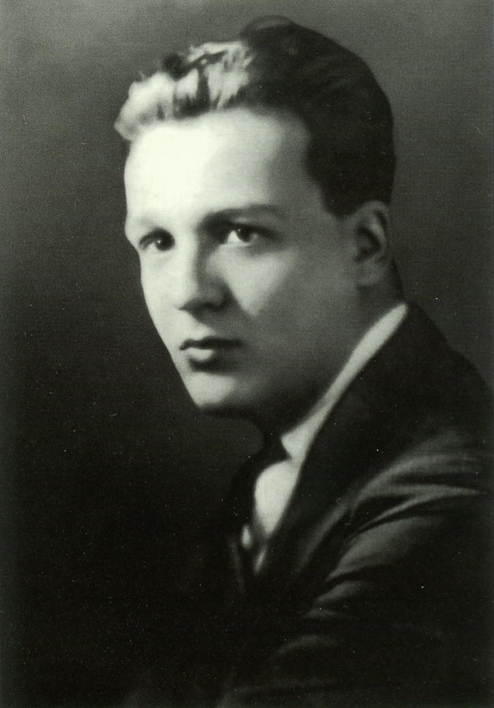

I ran across one comment by a fan that Sturgeon can be reckoned the greatest short story writer of the 20th century. Such hyperbole is forgivable, even among those of us who realize that such a thing could never be quantified. Sturgeon is great-- though he is himself dead, his writing is not a "was" but remains vibrant for anyone living now who discovers what he left behind for us. Sturgeon needs to be esteemed in this age that otherwise prizes puerile writing, when writers of his caliber are all but forgotten even among those who consider themselves "readers". This review will consider another of those short stories that seem "miraculous", and one that is vintage Sturgeon. It runs across nineteen pages, and covers more emotional, scientific, sociological, psychological, anthropological, political and philosophical territory than most series of novels do today weighing in at five-hundred pages per volume! And did I mention that the four main characters in this tale are utterly fascinating, and that the central character is utterly surprising? Before I summarize, let me just say this: if you have at least a workable lump of humanity on your mental potter's wheel, this story has the power to enable you to recognize spiritual kinship with someone you thought completely different from yourself. In short, it can turn ill-informed bigots (i.e., bigots who are so not because they like to be but because they have been brought up wrong), into sighted souls who realize the alien is not other but beloved self. This story first came out in 1953, and it was far in advance of many of the enlightened components of the counter-cultural movement that crystallized over a decade later. Indeed, recognizing that much of what that counterculture achieved for us in expanding our moral breadth has been undone in more recent decades of resurgent conservatism, there are few writers who can say with greater beauty and insight what Sturgeon said here in this tale, now almost sixty years ago. Okay, it's science fiction, but back in his day, science fiction writing (not the "B" Hollywood movies) was the place where some of the greatest explorations of the meaning of life were being imaginatively made, and Sturgeon was among the cream of the crop not merely as an idea man but in sheer writing skill. So in this story we have a couple aliens land on the Earth and make of themselves benign and appreciative visitors, who obviously are looking to find some niche where they can make a home for themselves. These two beings appear to be a mated pair, and have physical characteristics that resemble the most beautiful aspects of both birds and humans. They also emanate a love so morally appealing that it captures the imagination of the world, whose fascination is exploited commercially to the hilt. At this time in Earth's future history, humanity has resolved itself into rather focused forms of sensory exploration, the social castes being purely practical: a majority are consumers of sensation, a minority are creators of sensation, and an even smaller minority are the actual "doers" who make the machinery and conveyances of society function and perform. The two alien visitors, nicknamed "the loverbirds" by the media, are our first two main characters. However, the people of Earth soon learn that this pair of lovely visitors are fugitive criminals from a planet ("Dirbanu"), which many years before had established a policy of "no relations" with Earth after one accidental discovery by a Terran ship, and a single ambassadorial mission from that planet with a disappointing lack of rapport. Indeed, their planet is shielded with an unknown technology that not only prevents any one from landing on it, the shielding also blocks all scientific or espionagic ability to discover its nature. The culture of this future Earth, however, is mad to acquire any technological prowess which it itself lacks, and so the government of Earth is only too willing to cooperate with Dirbanu's request that the fugitives be extradited back to them; for the government of Earth hopes that, in so cooperating, it might ingratiate itself for some form of scientific exchange program. Now we come to our next set of main characters, Captain Rootes and Midshipman "Grunty", of whom the latter shapes our perspective for the remaining course of the story. These two men are recruited to form the crew for the spacecraft capable of speedily deporting the two fugitives, whose ability to be in any way criminal is nowhere evident to the perceptions and sensibilities of Earth people. Rootes and Grunty, both members of the "doer" caste, are at this point highly noted for their superior quality of teamwork and handling of space travel, and hold a perfect record in the discharge of all previous assignments. Both are loyal to their work and each other, though they are of surprisingly different personalities. This difference appears to be complementary however, and the government of Earth sends them on their strange new mission with complete confidence. Rootes, for all his professional competence, is a self-dramatizing, super-heterosexual, who is nevertheless unfulfilled in actually establishing a meaningful loving relationship among his endless round of romantic conquests whenever he is in port between missions. Grunty, who is so named for his extreme level of laconic expression, has a rich inner life, evidenced by his erudite and sophisticated reading material, a library that he transports with him on all his missions. It is also evidenced by the omniscient narrator's progressive focus on his mind, which has a richness of expression, despite the fact that it is never given utterance. The crisis arises however, when the two convicts in their transport evidence signs that they can read Grunty's profound and poetic philosophical thoughts, especially when he directs them sympathetically toward them. The problem is, Grunty does not want anyone to know of his inner life, which is not only his chiefest treasure, but his very means of sanity in terms of its privacy. The aliens they are deporting are highly sympathetic to his inner nature, but this is not enough for Grunty. The fact is, there is the probable threat that they will telepathically convey the nature of his inner life to the rest of their kind, and then this will possibly be revealed to his fellow Earthlings as relations form between the two planets, and it is with his fellow human beings that Grunty definitely does not wish to share these precious thoughts and feelings. Matters complicate from there, but it turns out in no way you might suspect. The ending has two parts; both are surprising, both are wonderful. I will reveal no more than that the ramifications of this story's ultimate revelations are something people in America badly need to understand today, in terms of learning to let go of our culture's special knack for needlessly persecuting certain social groups. This tale may most readily be found in the following recently published book: The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon, Volume VII. Published by North Atlantic Books. Copyright 2002.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment